INTRODUCTION

India has the second largest number of tobacco users in the world after China, with nearly 28.6% (266.8 million) of adults using tobacco1. Every year, tobacco use causes more than a million deaths in India2, leading to two in five (40%) of all cancer deaths, and 90% of all oral cancer deaths3,4. Direct and indirect costs of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality have been estimated at US$ 23 billion annually5; this exceeds the combined government and state expenditure on public health, water supply, and sanitation6.

India is one of the youngest countries in the world with 40% of its population of 1.3 billion below the age of 19 years7. Four in ten tobacco users in the country start before the age of 18 years8.While the national prevalence of tobacco use among adolescents aged 13–15 years is 15%9, school and community-based studies have reported a prevalence ranging from 11% to 46%10-14. Furthermore, the national mean age of initiating tobacco-use decreased from 18.5 years in 2009–2010 to 17.4 years in 2016–201715. In the state of Maharashtra, while the overall tobacco use prevalence has dropped from 31.4% to 26.6% between 2009–2010 and 2016–2017, the prevalence among those aged 15–17 years increased by 3% in the same period1,8. The current and intended tobacco-use among adolescents and youth will exacerbate the burden of the country’s tobacco-related morbidity and mortality; thus, making prevention efforts for adolescents critical in national tobacco control policies and programs.

Comprehensive, enforced tobacco-free school policies at the national and state level have shown significant decrease in tobacco use among adolescents and youth16. In 2003, the Parliament of India enacted the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act (COTPA); two of its provisions exclusively focused on protecting minors from initiating tobacco use such as: ban on sale of tobacco products to and by minors (persons below 18 years) and prohibition of selling of any kind of tobacco products within 100 yards (1 yard = 91.44 m) of all educational institutions17. In 2009, the National Ministry of Health and Family Welfare released comprehensive guidelines for achieving tobacco-free schools and educational institutions18. The Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) pushed this policy forward towards implementation by setting down 11 criteria for achieving a tobacco-free school (TFS), and making it mandatory for all its affiliated schools19. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) has further revised these guidelines in 201920. While this policy of ensuring schools use the TFS criteria aims to prevent and control tobacco use among students through information, by changing the organizational culture in schools, and creating norms among this age group to make it tobacco-free, it is the actual implementation of this policy that will ultimately lead to a tobacco-free society for Indian youth.

This study aimed to examine the effect of a teacher-training intervention in achieving tobacco-free schools in the state of Maharashtra, India. In doing so, it assessed the number of schools that implemented the 11 TFS criteria of the CBSE (Table 1) after receiving the teacher training-based intervention.

Table 1

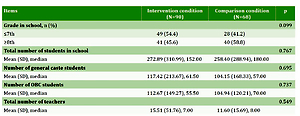

Comparison of schools in the intervention- and comparison-condition districts on various school-related parameters and tobacco-free school (TFS) criteria fulfilment

| Items | Intervention condition (N=90) | Comparison condition (N=68) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade in school, n (%) | 0.099 | ||

| ≤7th | 49 (54.4) | 28 (41.2) | |

| ≥8th | 41 (45.6) | 40 (58.8) | |

| Total number of students in school | 0.767 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 272.89 (310.99), 152.00 | 258.40 (288.94), 180.00 | |

| Number of general caste students | 0.695 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 117.42 (213.67), 61.50 | 104.15 (168.33), 57.00 | |

| Number of OBC students | 0.737 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 112.67 (149.27), 55.50 | 104.94 (120.21), 70.00 | |

| Total number of teachers | 0.549 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 15.51 (51.76), 7.00 | 11.60 (15.69), 8.00 | |

| Student/teacher ratio | 0.826 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 22.93 (8.91), 21.85 | 23.25 (9.34), 21.50 | |

| Number of years of principal in current school | 0.241 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 7.40 (8.71), 4.0 | 9.021 (8.04), 5.0 | |

| School has internet, n (%) | 0.545 | ||

| Yes | 52 (57.8) | 36 (52.9) | |

| No | 38 (42.2) | 32 (47.1) | |

| School has e-learning center or computer lab, n (%) | 0.088 | ||

| Yes | 67 (74.4) | 42 (61.8) | |

| No | 23 (25.6) | 26 (38.2) | |

| School has separate toilets for boys/girls, n (%) | 0.007 | ||

| Yes | 88 (97.8) | 59 (86.8) | |

| No | 2 (2.2) | 9 (13.2) | |

| School has a complete boundary wall or fence, n (%) | 0.331 | ||

| Yes | 50 (55.6) | 43 (63.2) | |

| No | 40 (44.4) | 25 (36.8) | |

| School has a functional playground, n (%) | 0.006 | ||

| Yes | 81 (90.0) | 50 (73.5) | |

| No | 9 (10.0) | 18 (26.5) | |

| School students participated in sports competitions in last academic year, n (%) | 0.217 | ||

| Yes | 82 (92.1) | 55 (85.9) | |

| No | 7 (7.9) | 9 (14.1) | |

| School students participated in extra-curricular competitions in last academic year, n (%) | 0.418 | ||

| Yes | 68 (87.2) | 51 (82.3) | |

| No | 10 (12.8) | 11 (17.7) | |

| Number of workshops attended by teachers in last academic year | 0.000 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 2.79 (3.06), 2.00 | 6.84 (6.44), 5.00 | |

| Teachers of the school who have won awards | 0.837 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 0.78 (1.13), 0.00 | 0.84 (1.48), 0.00 | |

| TFS total score (out of 11) | 0.000 | ||

| Mean (SD), median | 7.76 (3.88), 10.00 | 1.12 (2.74), 0.00 (Mode=0) | |

| Categorization of schools into three groups based on number of criteria fulfilled, n (%) | 0.000 | ||

| All 11 | 34 (37.8) | - | |

| 07–10 | 31 (34.4) | 9 (13.2) | |

| ≤6 | 25 (27.8) | 59 (86.8) | |

| The 11 TFS Criteria (C1-C11)* | Intervention condition n (%) | Comparison condition n (%) | p |

| 1. No tobacco being used inside the school. No chewing or smoking of any tobacco product in premises of school by staff, students, and visitors | 69 (76.7) | 10 (14.7) | 0.000 |

| 2. Tobacco control committee is in place in the school and quarterly meetings are conducted of the same | 67 (74.4) | 9 (13.2) | 0.000 |

| 3. Display of appropriate signage in the school stating that smoking or tobacco use is not permitted in and around the school premises | 72 (80.0) | 9 (13.2) | 0.000 |

| 4. Posters with information on harmful or ill-effects of tobacco inside the school premises | 63 (70.0) | 8 (11.8) | 0.000 |

| 5. School stationary has tobacco-use prevention related messages | 63 (70.0) | 1 (1.5) | 0.000 |

| 6. Principal has a copy of directives/circular based on the 2003 law (COTPA document) | 57 (63.3) | 8 (11.8) | 0.000 |

| 7. State nodal officer for tobacco has been contacted for help and/or school has officially availed itself of any advice through consultation regarding tobacco prevention with any state-appointed tobacco control advisor/doctor/dentist | 58 (64.4) | 1 (1.5) | 0.000 |

| 8. Integration of tobacco control activities with on-going or regular school health activities or school health program | 65 (72.2) | 9 (13.2) | 0.000 |

| 9. No sale of any tobacco product or tobacco selling completely banned within a radius of 100 yards from the school/educational institution | 64 (71.1) | 10 (14.7) | 0.000 |

| 10. The school has recognized and awarded any tobacco prevention or control efforts by staff or students | 58 (64.4) | 1 (1.5) | 0.000 |

| 11. Display of a board or banner near the entrance of the school (in a prominent and visible place) which states that this is a tobacco-free education area or tobacco-free school | 62 (68.9) | 10 (14.7) | 0.000 |

METHODS

Study setting and design

Maharashtra is one of the five major tobacco-producing states in India, with 16.7% of total agricultural land (1950 hectares) used for tobacco cultivation21. It is the second most populous state in the country with 35 administrative districts; districts are further broken into administrative blocks and Gram Panchayats (village units). The government manages 68% of the total 100084 schools in the state, all of which are expected to comply with the state tobacco control policies. Around 20% of schools are privately owned but receive government aid for operations, and 12% are completely privately owned and operated. A total of about 13.7 million students, mostly from families with lower socioeconomic status, attend government-managed schools. Government schools have a rigid bureaucratic structure, inadequate infrastructure, low teacher motivation that translates into lower expectations from students, which ultimately affects their school performance22,23.

Despite the existing TFS policy measures since 2009, government schools in the state have struggled with understanding and implementing tobacco-free schools24. Salaam Mumbai Foundation (SMF), a non-governmental organization (NGO) that works to prevent tobacco use among children, collaborated with the State Education Department to train teachers to implement the TFS policy25,26. This study used a post-only quasi-experimental design to gather information on the fulfillment of the 11 TFS criteria (Table 1) from randomly selected upper-primary (5th to 7th grade) and secondary (8th to 10th grade) government schools in four districts in Maharashtra. Of the four predominantly rural districts, 2188 upper-primary and secondary schools, in the two intervention districts combined, received a TFS teacher-training intervention, once every year for five years starting in the academic year 2013–2014. Two districts, with 1707 upper-primary and secondary schools, served as comparison districts, and the intervention was not provided to them. A quasi-experimental design was used as it was not possible to randomly assign schools to intervention and comparison conditions; hence, the entire sample of upper-primary and secondary schools in the intervention districts were allocated to the intervention. It was also not possible to randomly assign districts; however, an administrative decision to conduct training in phases led to the circumstances for a natural experiment, when it was found that two comparison districts were left out of the training for a few years. At the end of five years, between January and March 2018, trained observers visited 200 randomly selected schools from among all the eligible schools in all four districts.

Intervention

This intervention trained one designated teacher from each selected school in the intervention districts, to fulfill each of the 11 TFS criteria. An official letter was sent from the Department of Education to each school explaining the intervention and subsequent activities in the school. The principal or headmaster was requested to designate one teacher who was not a tobacco user and had demonstrated motivation to work on health and school-development activities. Teacher training has been found to have a significant effect on implementation of school-based tobacco control programs27. This intervention used a cascade model, wherein five motivated teachers served as master trainers for each administrative block and then trained the designated teachers within their respective block. On average, each district has roughly 10 administrative blocks, bringing the total number of master trainers between 50 and 60. Master trainers in each district were trained over a period of two days by SMF staff in the district headquarters. Block Education Officers (BEOs) sent official letters to principals of each school in their respective blocks requesting them to nominate or designate one teacher to receive the TFS training intervention and become the point-person for TFS policy implementation in the school. The curriculum of the teacher-training intervention consisted of four sessions delivered in one working day. The sessions were: introduction to the problem and burden of tobacco and its harmful consequences; how to prevent initiation of tobacco use and provide cessation support; and COTPA laws and how to implement the 11 TFS criteria. This training employed pedagogic techniques appropriate for adult learners, using lectures, discussions, role plays, audio-visual aids, and PowerPoint slides, making the learning emphatic and interesting. Group work helped identify the optimum local ways to fulfill TFS criteria in these schools.

Sampling and data collection

A multi-stage sampling method was used. First, SMF staff, with help from district administration, identified two blocks in each district; the first was relatively more urbanized and around the district headquarters, the second block was rural and geographically distant from the headquarters. Then, 25 schools were randomly selected in each of the two designated blocks of the district, from a list of all government schools provided by the BEO. A total of 200 schools were thus shortlisted from eight blocks in the four districts. SMF recruited two observers, from each district, who were trained rigorously to understand and apply an instrument with two sections. These observers were experienced social workers on the staff of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in the four districts; one NGO was engaged in each of the four districts for the purpose of conducting the research. School visits in each district were conducted within a ten-day period. Since BEOs or school principals were not aware of the final list of schools, the chance of them informing others about impending visits and possibility of any systematic overestimation of adherence was highly unlikely.

Study instrument

The study instrument had two sections. The first section was a checklist to observe the school’s adherence to the 11 TFS criteria, which were taken from the Central Board of Secondary Education’s (CBSE) eleven criteria for a tobacco-free school (TFS) mandatorily to be followed by all its affiliated schools. These 11 criteria provide direct information on: information materials in the school such as posters and signage; whether schools maintain a copy of the COTPA law; enforcement of the banning of sale and use of tobacco in and around schools; organization culture vis-à-vis tobacco control committees, regular activities, awards for their tobacco control efforts; and calls for convergence with health department by asking schools to consult with the state tobacco control officers24.

The second section of the instrument collected information on school-related variables such as numbers of students and teachers, infrastructure and amenities, and participation in competitions, workshops and teacher-awards. Trained observers used the checklist of these 11 criteria (Table 1) and assessed adherence to each criterion using a No or Yes (0, 1) scale. Data on school-level indicators were gathered from the principal or an assigned teacher to examine whether schools in the different conditions differed significantly on some basic parameters. The study was approved by the Review Board of Salaam Mumbai Foundation. Prior consent was obtained from the State Department of Education and its district and block level units, and from the principals or headmasters of the selected schools.

Data analysis

Data were entered in Microsoft Excel 2007, and then analyzed using the SPSS software version 16.028. First, data were checked for completeness. Of the 200 schools in the sample, data on TFS criteria checklist were complete for all schools, but data were missing for some school-level variables for 42 schools. Thus, the response rate with fully completed surveys was 79%; the reasons for incompleteness of data were the absence of the headmaster or principal on that day, or the principal or headmaster being on leave and the teachers present being unable to provide the required information. These 42 schools with incomplete school-level data were removed from the sample leaving a total of 158 schools – 90 in the intervention districts and 68 in the comparison districts – with complete data on both TFS criteria checklist and school-related information. Second, descriptive frequencies for adherence to each of the 11 TFS criteria and school-level variables were generated. Since adherence to a TFS criterion was scored as 1 and non-adherence as 0, a new variable was computed to identify the total score for each school on TFS criteria fulfillment with a maximum of 11 and minimum of zero. The t-test was employed to check for differences in mean scores for schools in either of the two conditions (intervention or comparison). The TFS score, an interval-level variable, was recomputed as a nominal variable with three categories: TFS score of 11; TFS score of 7–10; and TFS score of ≤6. All variables – TFS scores and school-level variables – were compared for the two conditions. Comparisons were conducted by t-test (independent samples, separate variance estimates) for continuous data and chi-squared tests with Yates’s correction for discontinuity where appropriate for nominal data. Significance levels were set at 5%, two tailed, for all analyses.

RESULTS

Description of school-level indicators

Nearly 55% (49) and 41.2% (28) of the schools in intervention and comparison conditions, respectively, were up to 7th grade and the rest were 8th to 10th grade (p=0.099).

Composition of students and teachers

The average number of students in the intervention schools was 272.9, and 258.4 in the comparison schools (p=0.767). The mean number of general caste students and other caste students was not significantly different in intervention and comparison groups, and so was the average number of teachers in intervention and comparison schools. Schools in both the conditions had one teacher for roughly every 23 students. The number of years spent by the principal in the school were 7.40 and 9.02 years for the intervention and comparison schools, respectively (p=0.241).

Infrastructure and amenities

Although the intervention districts had a higher proportion of schools with an e-learning center and internet, comparison districts had a higher proportion of schools with a boundary wall or fence, these differences were not statistically significant. However, schools in the intervention condition were significantly more likely to have separate toilets for girls (p<0.007) and a functional playground (p=0.006) relative to comparison schools.

Extra-curricular performance

The differences among intervention and comparison schools were not statistically significant with respect to participation in inter-school sports competitions and extra-curricular events in academic year preceding the study. However, the number of workshops attended by teachers in the last academic year was significantly lower (mean 2.79; median 2) for intervention district schools compared to comparison schools (mean 6.84; median 5) (p=0.000). The number of teachers who had won awards were not significantly different between schools of both conditions.

Tobacco-free school (TFS) criteria

In intervention schools, the average total TFS criteria-fulfilment score out of a maximum possible of 11 was 7.76 (median 10; mode 11) compared with 1.12 (median 0; mode 0) for schools in the comparison condition (p=0.000). The TFS score interval variable was recomputed into a nominal variable with three categories: 11, 7–10, and ≤6 criteria fulfilled; and 37.8% (n=34) of intervention schools had achieved all 11 TFS criteria compared to none in the comparison condition. Among intervention schools, 34.4% (31) attained scores 7–10 and 27.8% (25) reached ≤6, compared to 13.2% (9) and 86.8% (59) schools, respectively, in the comparison condition (Table 1).

Greater than 70% of intervention schools had implemented seven of the individual criteria such as: C1 – No tobacco being used inside the school, i.e. no chewing or smoking of any tobacco product in the premises of the school by staff, students, and visitors; C2 – Tobacco control committee is in place in the school and quarterly meetings are conducted of the same; C3 – Display of appropriate signage in the school stating that smoking or tobacco use is not permitted in and around the school premises; C4 – Posters with information on harmful or ill-effects of tobacco inside the school premises; C5 – School stationary has tobacco-use prevention related messages; C8 – Integration of tobacco control activities with on-going or regular school health activities or school health program; and C9 – Tobacco selling completely banned within a radius of 100 yards from the school/educational institution (Table 1). Less than 70% and greater than 60% of intervention schools had implemented the following criteria: C6 – Principal has a copy of directives/circular based on the 2003 law (COTPA document); C7 – State nodal officer for tobacco has been contacted for help and/or school has officially availed itself of any advice regarding tobacco prevention through consultation with any state-appointed tobacco control advisor/doctor/dentist; C10 – The school has recognized and awarded any tobacco prevention or control efforts by staff or students; and C11 – Display of a board or banner near the entrance of the school (in a prominent and visible place) that states that this is a tobacco-free education area or tobacco-free school.

In the comparison schools, ≤14% of the schools had been able to implement any particular criterion. The criteria that showed the greatest difference in implementation between intervention and comparison districts, where only one school in the comparison condition had implemented it, were: C5, C7 and C10.

TFS criteria fulfilment in intervention schools in score category of 7–10

A detailed examination of 34.4% schools in the intervention condition that fulfilled 7 to 10 criteria was conducted to reveal which criteria of the 11 remained difficult to attain. Nearly two out of five (38.7%) schools in this category were unable to fulfil C11, the 11th criterion that required the school to ‘display a board or banner near the entrance of the school stating that this is a tobacco-free school’. Some other criteria difficult to fulfil by these schools (in descending order from high to low) were: C10 (29%), C6 (29%), C7 (25.8%), C1 (25.8%), and C2 (22.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2

TFS criteria difficult to fulfil for intervention schools in the TFS score category of 7–10 criteria fulfilled (intervention schools only, N=90)

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study, a post-only quasi-experimental design, is one of the first studies to systematically examine the effect of an intervention to make government schools tobacco-free in entire districts using TFS criteria laid down by a government agency. Findings from this study have implications for tobacco-control and school-health practitioners and policymakers. In two intervention districts, all schools were included in a teacher-training TFS intervention, while two similar districts, where for administrative reasons no intervention was offered, served as comparison in a natural experiment. The mean number of TFS criteria met by the schools (TFS score out of a maximum possible of 11) in the intervention districts was 7.76, which was significantly higher than 1.12 in the comparison districts. The proportion of schools in the intervention districts that completed all the 11 TFS criteria (37.8%) was significantly higher than in the comparison districts, where none of the schools had achieved scores of 11. Around 34.4% of schools in the intervention districts and only 13.2% of schools in the comparison districts completed between 7 to 10 criteria; whereas 27.8% of schools in intervention districts compared with 86.8% of schools in comparison districts fulfilled ≤6 criteria.

Despite the recent 3% increase in the national tobacco-use prevalence among those aged 15–17 years and the decrease in the mean age of initiating tobacco use from 18.5 years to 17.4 years1,15, compliance with the national tobacco control law (COTPA), especially the provisions focusing on adolescents, remains inadequate29. Studies that quantitatively assessed compliance with the TFS criterion prohibiting sale of tobacco within 100 yards in schools in India, reported weak implementation30,31. Chatterjee et al.24 examined compliance with the 11 TFS criteria in Maharashtra and found that only 11% of 507 government-affiliated schools had fulfilled all the criteria; 80% had a score between 1 and 10; and 9% of schools did not fulfil any of the criteria. Compared to the 11% of all schools in the previous study, 37.8% schools in the present study showed adherence with all 11 TFS criteria, making it very likely that the teacher-training intervention had a positive effect on making these schools tobacco-free.

However, the question remains as to why this intervention only facilitated 37.8% in attaining all TFS criteria. While this study did not examine the barriers to adherence with all TFS criteria, a previous qualitative study revealed factors such as disinterested teachers, lack of ownership by the school management and community norms surrounding tobacco use as barriers to fulfilment of TFS criteria, and that teachers, who successfully made their school tobacco-free, were driven by a personal mission of tobacco-eradication or drive for social change25. Future teacher training will need to incorporate methods to reinforce and sustain this sense of purpose. During training sessions, teachers could be categorized into groups based on an assessment of skill and motivation levels, and each category provided with appropriate content and amount of instruction and support to achieve TFS.

A closer examination of the hard-to-attain criteria, among 34.4% of intervention schools that fulfilled between 7 and 10 TFS criteria (Table 3), could help shed light on the difficulties in reaching 100% compliance. Nearly two out of five (38.7%) of the 7–10 score category intervention schools were unable to fulfil the last criterion, which required them to display a board near the entrance of the school stating this is a tobacco-free school. It is likely that many schools felt it was necessary to complete all other criteria before displaying such a board. However, this criterion requires clarification in future training because a display board demonstrates the intent of the school to everyone. This board also reinforces the message among students, teachers, visitors, and community members, that tobacco use is not permitted by law and is neither desired nor permissible in the school, which is one of the major institutions of that community.

Some of the other unfulfilled criteria (Table 2) can be met through follow-up meetings after the teacher-training intervention. Schools can be provided with a copy of the law or supported to contact a state-level officer for tobacco-related consultation. School principals can also be encouraged to institute special awards for tobacco control efforts. However, it is a concern that someone, a teacher, visitor, or student, is still using tobacco on the premises in one in four schools (25.8%), and this requires focused action from the State Education Department.

Mere provision of training to teachers seems inadequate as an intervention, if Maharashtra desires to reach the goal of 100% tobacco-free schools in an accelerated manner. Additional intervention components will be critical to ensure that the tobacco-free status of a school is sustained after adoption. These components can include: follow-up sessions after training, either face-to-face or through mobile/digital contact; closer monitoring by block-level officers of the Department of Education; establishment of a feedback mechanism between the school, Department of Education and an NGO, such as SMF, using digital technology. Finally, a formal and official reward and recognition system has to be instituted. One possible strategy to ensure that these recommendations are realized in these government schools in the state of Maharashtra is by linking this program with the central government’s larger platform of school health program launched under its flagship the Ayushman Bharat initiative32. This central government-backed school health program aims to provide health education, disease prevention, promotion of healthy behaviors, and access to health services by children and adolescents. Linking tobacco control recommendations, particularly the teacher training activities, could prove effective in reaching and ensuring completion in schools across the state.

Limitations

Although use of schools in two different conditions, intervention versus comparison, makes the design stronger to some extent, this study has its limitations. One deficiency is the absence of a pre-test with which to compare the post-test findings. While it is possible that intervention districts already had high proportions of adherent schools at baseline, data from other studies seem to indicate that only 11% of schools were compliant in a large-scale assessment of TFS criteria in schools across the state24.

Furthermore, we cannot affirm with absolute certainty that the comparison schools received any intervention at all; to the best of our knowledge, they did not. Similarly, the intervention schools also did not receive any additional inputs from other sources. Data collection relied on observations of TFS criteria fulfilment by different observers in the four districts. This might be a source of error, especially arising from an improper understanding of the criteria by different observers. Partial reliance on self-report by a designated school representative to obtain data on school-level variables could also be a source of bias. Training and supervision of observers during data collection addressed these possible sources of bias. Data were collected from government-run schools in rural areas of Maharashtra making the findings difficult to generalize across all schools or states in India. While this study did not explicitly capture community-level factors, it did look at amenities and infrastructure, which are often a reflection of the effectiveness of school management committees that include local community leaders.

CONCLUSIONS

If the stakeholders of the TFS program aspire to make 100% of the schools in Maharashtra tobacco-free, then future efforts will have to rely on implementation research techniques33 in order to clearly identify specific factors that facilitate or hinder schools from implementing the 11 criteria of the TFS policy. Workshops can facilitate decision-making on TFS criteria to be retained or removed from the current list. However, a deeper understanding of the challenges in the implementation process can support policy-makers and practitioners to adapt existing strategies or develop new approaches to increase the proportion of tobacco-free schools, as well as accelerate the adoption and sustainability of TFS criteria, thereby creating a tobacco-free environment for children.