INTRODUCTION

Since the early 1970s, dental professionals have become increasingly aware of the damage that smoked and smokeless tobacco causes to tissues in and around the oral cavity1-5. Ranging from mild to life-threatening, the following tobaccorelated oral conditions may develop: halitosis, hairy tongue, dental calculus, periodontal disease, acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, abrasion, discolouration of teeth and restorative materials, miscellaneous tissue changes, delayed wound healing, sinusitis, leukoplakia, and oral cancer. A critical appraisal of the literature suggests that behavioural intervention for smoking cessation involving oral health professionals is an effective method of reducing tobacco use in smokers and users of smokeless tobacco and preventing initiation in non-smokers6.

The dental team is well placed to undertake public health interventions; involvement would mean a radical change of approach to practice for most dentists and their teams. The adoption of such changes is likely to be determined by two main factors: whether the profession dental team can play a more general public health role, and whether it is economically possible for a dental team to make this change7. However, dental students and dental team members are in an ideal position to give their patients specific and authoritative information concerning the adverse oral effects of tobacco use. Available evidence suggests that interventions for tobacco cessation by non-physicians, including oral health professionals, may increase tobacco abstinence rates8,9, but incorporation of tobacco cessation counselling into dental practice has been slow10. Most dentists tend to ask new patients about smoking behaviours, but few engage in active cessation efforts or refer patients to a cessation program11-14. The main barrier to cessation counselling is lack of smoking cessation experts to refer to; other barriers are a lack of reimbursement, a lack of knowledge, time constraints, and a feeling of inadequacy15.

India is the fourth largest consumer of tobacco after China and Brazil. There are about 250 million tobacco users in India accounting for about 19% of the world’s total 13 billion users16. Tobacco use can lead to death, as it is one of the causes of chronic diseases. In 2005 tobacco use resulted in an estimated 5 million deaths worldwide and this number is expected to increase to 10 million deaths per year by 202017. Dental professionals are in a unique position to identify the effects of smoking on oral health early on, and can provide suggestions and advice to smokers about the need to prevent or quit smoking, offering advice and help that is quick, simple and tailored to the patient18. However, research has shown that dental patients now expect oral health professionals to inquire about their tobacco use19. As more information on dentally oriented tobacco cessation research was published, dental institutions were encouraged to start formal programs20,21.

The current study examines the attitudes of dental students towards tobacco cessation counselling, whether prescriptions for quitting were in their scope, and the existing barriers to giving quitting advice.

METHODS

A cross-sectional self-administered questionnaire study was conducted among 200 dental students of Andhra Pradesh, India. Questionnaires were distributed, the purpose of the study was explained, and filled in forms were collected, at the same time. Demographic data, including age and gender, were collected. Fourteen questions from a study of Victoroff et al.22 with respect to the attitudes towards tobacco cessation were taken for this study and used to evaluate attitudes in the areas of professional responsibilities, the scope of cessation counselling practice and outcome assessment. Apart from these, additional five questions, on perceived barriers to providing tobacco cessation were derived from the study of Yip et al.23. The items consisted of statements and a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from strongly agree to disagree strongly.

Within the attitude variables, exploratory factor analysis was performed to determine underlying dimensions. A composite attitude variable was derived for each factor using mean score of all retained items. Principle-component analysis with varimax rotation was used to identify interitem associations, to check for rudimentary items, and to establish underlying constructs among items. Internal consistency and reliability were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. When tested for sampling adequacy with KaiserMeyer-Olkin (0.732) and Bartlett’s test, it was found to be significant (p<0.001). The communalities of all factors are also less than 1, showing that the sample size and study factors included are adequate.

RESULTS

The role of dentists in smoking cessation

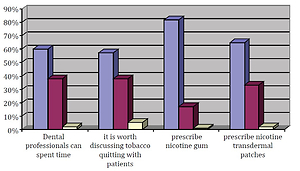

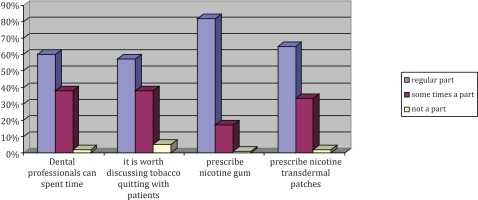

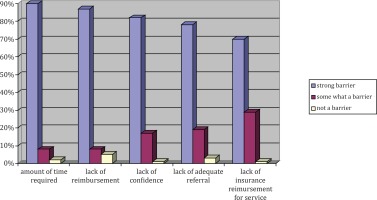

The study involved 62 male students and 138 female students for a total of 200 responses. Mean age of dental students who participated was 22.2±0.5 years. With reference to responsibility to educate the patient about tobacco smoking risks to overall health and well-being, 75% were in strong agreement, 79% strongly agreed to educate patients about the risks of tobacco on oral health, and 81% were in strong agreement to encourage patients to quit tobacco use. On questions related to attitudes of students about tobacco cessation counselling to advise quitting tobacco, discussing health hazards, and referring to cessation clinics, more than 50% were in substantial agreement. Lengthy clinical procedures and lack of time to give cessation counselling at the dental office were the main barriers among 66% of study subjects. Patient resistance to quitting tobacco was also another strong barrier identified by 52% students. Figure 1 shows the scope of dental professionals to give tobacco cessation counselling at their clinics, with 60% being of the opinion that it could be done as a regular part of the practice. Regarding tobacco cessation counselling at their clinics, 57% were of the opinion that it could be done as a regular part of clinical practice; perceptions on the provision of prescribing nicotine gum (82%) and nicotine transdermal patches (65%) were also high in their opinion. Figure 2 shows the opinions regarding barriers for the provision of smoking cessation services in their future regular practice where barriers included: amount of time required, lack of reimbursement, lack of confidence, lack of adequate referral knowledge, and lack of insurance reimbursement for services.

Table 1

Perceptions of dental students towards smoking cessation, Andhra Pradesh, India (N=200)

Identification of essential domains related to smoking cessation

Two principle-component analyses were conducted. In the first analysis with 20 items, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett’s test showed a sampling adequacy of 0.70 and significance with p<0.001. Five components with eigenvalues >1 were identified, with a total variance of 60.59%. The item with lowest loading on the first component was found to have lowest corrected item and total correlation, and lowered internal consistency. The third, fourth and fifth components with 10 underlying items were discarded owing to limited internal consistency reliability (Cranbach’s alpha <0.7). In total, 11 items were removed, and 9 were retained for further analysis. In the second analysis with 9 items, the KaiserMeyer-Olkin and Bartlett’s test showed sampling adequacy of 0.732 and significance with p<0.001. Two components were found with eigenvalues >1. The total variance was 60.6%. The internal consistencies for the two components were 0.81 and 0.78, respectively. Hence, the original Victoroff et al.22 instrument, divided them into three domains, professional responsibility, scope of the dental practice, and effectiveness. Principle-component analysis of our data revealed that effectiveness remained as a discrete factor. Professional responsibility and scope of dental practice collapsed into one factor, which we have identified as scope and responsibility. A fourth factor, identified as prescriptions, also emerged as a significant domain.

DISCUSSION

Findings of our study were that the psychometric properties of the two instruments are of high quality, adding credence to previous reports based on these instruments. Overall, more than 70% of respondents were in strong agreement that the dental profession has a responsibility to educate patients about the risks of tobacco use and to encourage patients to quit smoking. These findings are similar to those of previous studies20,21. It shows a willingness on the part of dental students to consider incorporating tobacco cessation counselling into their future practices. The majority of students in this study were in substantial agreement that specific actions, such as the ‘5 As’ of smoking session (ask, advise, assess, assist, arrange) were within the scope of dental practice. Research has found that rank ordering of the ‘5 As’ is consistent across groups of health care providers, with asking about tobacco use being most prevalent, followed by assisting and arranging22. On the question whether tobacco cessation counselling offered in the dental office could have an impact on patients’ quitting, 57.2% believed that it could as a regular part of dental practice, this was higher than in other studies where 15% of the respondents agreed that tobacco counselling could encourage patients to quit tobacco23. Regarding the barriers to expanded efforts, the majority believed that time constraints were a significant factor in providing this service as well as the lack of confidence in ability to help patients quit. Lack of adequate referral knowledge was also thought a barrier. More than 50 per cent mentioned lack of insurance reimbursement for services as a substantial barrier to provision of tobacco cessation services. The Cochrane review concluded that behavioural tobacco cessation interventions delivered by dental professionals might increase abstinence rates among cigarette users and smokeless tobacco users24. However, many dentists do not engage in tobacco cessation counselling efforts with their patients25,26. A significant barrier is the lack of tobacco-dependence education during dental training27. As part of integrating tobacco cessation into dental education, numerous researchers have examined dental student attitudes towards tobacco cessation28-31. At the time the original Victoroff et al.22 instruments were constructed, nicotine replacement was the only prescription pharmacological intervention available. Our analysis supports the idea of prescription writing for tobacco cessation activities within the scope of dental practice. This is consistent with the Victoroff et al.22 contention that dental students may be comfortable with providing general information and education, but not with becoming actively involved in the cessation process.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, more than 70% of the participating dental students were in strong agreement that the dental profession has a responsibility to educate patients about the risks of tobacco use and to encourage patients to quit smoking. It was clearly evident that dental students were in acceptance of tobacco cessation counselling as an integral part of oral health delivery. Further research should support its incorporation into the dental curriculum and dental practice. Development of strategies to integrate tobacco cessation counselling within the dental profession is a crucial aspect, supported also by this study.