INTRODUCTION

Antiretroviral therapy (ART ) has saved lives and improved quality of life among people living with HIV (PLHIV)1. Globally, 12.1 million AIDS-related deaths have been averted since 20101. In the Netherlands, an estimated 14449 deaths caused by, associated with, or exacerbated by HIV/AIDS were averted during 2010–20161. Life expectancy among PLHIV has risen to that seen in the general population2. The Netherlands in particular has made huge strides in HIV care; from an ART coverage of just 43% in 20001, Netherlands rose to become one of only 14 countries in the world to meet the 90–90–90 targets by the end of 20193. These targets, developed by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), aimed to increase the percentage of PLHIV diagnosed, the percentage on ART among those diagnosed, and the percentage virally suppressed among those on ART, to ≥90% within each indicated population by 20204. In addition, the Netherlands was the only EU member state to reach far in advance, the 2030 target of achieving viral suppression among ≥95% of those on treatment3. As ART coverage has increased, a corresponding decrease has been noted in onward transmission rates. The HIV incidence rate in the Netherlands decreased from 7.7 cases per 100000 population to 3.3 cases per 100000 during 2010–2019, one of the largest declines seen in the EU in terms of relative change (59.6% decrease)5.

Despite dramatic progress, unmet needs remain with daily oral HIV treatment. Four main categories of these unmet needs have been identified in previous research, including emotional challenges (i.e. concerns or worries) about immediate-, short-, or long-term impacts of treatment; and psychosocial challenges from stigma, various barriers to adherence, and conditions that made daily oral administration challenging (e.g. comorbidities, or risk of drug-drug interactions from co-medications)6. In 2019, 11.8% of Dutch PLHIV in one study reported suboptimal adherence to treatment because of various medical and non-medical factors7.

In December 2020, the European Medicines Agency granted authorization for the first long-acting regimen (LAR) for HIV treatment comprising two treatments – rilpivirine and cabotegravir8. Administered every two months, LAR creates an option for PLHIV to opt for non-daily dosing9,10. To optimize the potential for this novel treatment to help improve quality of life among PLHIV, it is important to identify which segments of the PLHIV population perceive they would benefit the most from non-daily treatment. Three defining criteria of an innovative drug are therapeutic need, added therapeutic value and the quality of the evidence. While the third criterion (quality evidence) has been well demonstrated in clinical trials showing non-inferiority between LAR and daily oral dosing9,10, subjective assessments from PLHIV are needed to assess perceived therapeutic need and added therapeutic value from the patient’s perspective. Therefore, this study had two key objectives: 1) explore PLHIV’s preference for long-acting treatment in the overall population of sampled PLHIV and what factors were associated with these preferences (i.e. perceived therapeutic need); and 2) explore what factors explain the higher LAR preference among those perceiving room for improvement with their HIV treatment versus those without perceived room for improvement (i.e. perceived added therapeutic value).

METHODS

Study population/sampling approach

Data for this study came from the second wave of the Positive Perspectives Survey (PP2) conducted in 25 countries (n=2389), including 12 European countries (n=969) during 20197,11–15. Web-based surveys were administered to adults aged ≥18 years with confirmed HIV status. PLHIV were recruited from existing panels of confirmed HIV seropositive individuals; national, regional, and local charities/support groups; as well as from online/social media platforms. The participating countries in Europe were the Netherlands (n=51), Austria (n=50), Belgium (n=50), Poland (n=50), Republic of Ireland (n=50), Switzerland (n=55), Portugal (n=60), France (n=120), Germany (n=120), Italy (n=120), Spain (n=120), and the UK (n=123).

Measures

Definitions of various clinical and demographic constructs in the survey were consistent with previous PP2 studies, including measures such as self-reported viral status11, polypharmacy11, suboptimal ART adherence7, self-rated health11, treatment satisfaction16, and perceived importance of various ART improvements/attributes17. Survey participants who answered ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ to the statement ‘As long as my HIV stays suppressed, I would prefer not having to take HIV medication every day’ were classified as indicating preference for non-daily regimens (i.e. LAR).

Detailed measurements of the four broad categories of unmet needs outlined within the main study objectives are presented below.

Emotional and other challenges associated with daily oral ART

The survey assessed treatment-related challenges, including participants’ worries and concerns about HIV and HIV treatment. Specific emotional challenges assessed included a report of being worried about the risk of drug-drug interactions, the potential effect of ART on their overall well-being, long-term side effects, and having to take more and more medicines with age. Other concerns included perceived stress from their daily ART dosing schedule, the perception that their daily ART dosing schedule limited their life, that daily dosing cued bad memories, or that daily dosing served as a daily reminder of their HIV status. As a proxy for the number of emotional stressors, we tallied the different indicators on which participants responded in the affirmative (range: 0–8), which was then classified into three categories based on tertiles (low, moderate, and high burden of emotional challenges).

Privacy and psychosocial issues associated with daily oral ART

The survey assessed participants’ attitudes and behaviors towards sharing their HIV status with others, hiding of their HIV medication to prevent others from knowing their HIV status, concerns regarding inadvertent disclosure of their HIV status, and perceived stigma. As a proxy for the number of stigma stressors, we tallied the different reasons for which participants ever refused to share their HIV status to avoid discrimination (range: 0–10). These reasons included anxiety over the prospect of any of the following 10 things happening to them simply because of their HIV status: ‘criminal prosecution’, ‘being denied access to financial benefits/support’, ‘my physical safety/potential violence’, ‘being denied access to health care services’, ‘it might affect my friendships’, ‘I might lose my job’, ‘it might affect my romantic or sexual relationships’, ‘I might be excluded from activities’, ‘they would see or treat me differently’, and ‘they might then disclose my HIV status to others’. The tally of reasons for nondisclosure was then classified into three categories based on tertiles (low, moderate, and high levels of anticipated stigma).

Daily oral ART and challenges with adherence

The survey assessed the frequency and reasons for which PLHIV failed to take their HIV medications within the past month. As a proxy for the number of adherence barriers, we tallied the different reasons for which ART was missed for at least once in the past month (range: 0–15). These reasons were: depressed/overwhelmed; to forget about having HIV; bored of taking pills every day; to avoid side effects; work; busy; to reduce risk of long-term side effects; issues with dosing requirements such as meals; substance use; had no pills; trouble swallowing pills; privacy concerns; traveling/away; could not afford pills; or other. The tally of reasons for missing ART was then classified into three categories based on tertiles (low, moderate, and high perceived barriers to adherence).

Medical conditions making daily oral ART challenging

From a list of 21 health conditions, participants were asked to select which conditions they had ever been diagnosed of, and for which they were currently taking medicines at the time of the survey. From these data, we created a tally of non-HIV conditions participants had ever been diagnosed with, as well as conditions for which they were currently taking medicines at the time of the survey; these were both categorized as 0, 1 only, or 2+. The medical conditions assessed in the survey included some known to make daily oral ART administration challenging including dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), gastrointestinal diseases (e.g. Crohn’s disease), and neurological, psychiatric, and behavioral disorders which might make it challenging for people to remember to take their daily dose at the right time.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed, and statistical significance of within-group differences were assessed using chi-squared tests. Prevalence difference (PD) between groups was expressed as absolute percentage points. In quantifying the burden of the various categories of unmet needs, overall estimates were from the Netherlands-specific data while stratified/comparative analyses were with pooled European data (including Netherlands) to increase sample size. Within each domain of unmet need, we examined the bivariate relationship between specific indicators of unmet need and LAR preference; we also examined adjusted relationships between LAR preference and aggregate measures of extent of unmet need within the respective domains, categorized as tertiles (low, moderate, high). Across all domains, we further measured the number of domains with unmet needs by computing a tally (range: 0–4) for whether the following were present: 1) moderate or high ART-related emotional challenges, 2) moderate or high levels of anticipated stigma, 3) moderate or high number of adherence barriers, and 4) having been diagnosed with at least one non-HIV comorbidity. Adjusted prevalence and odds ratios were calculated to measure associations, controlling for age and gender. Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition analysis was performed with the pooled European data to examine how much of the difference or gap in HIV-related perceptions, including LAR preference, between those with versus without the perception that there was room for improvement with their ART, was attributable to the various types of unmet needs. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS, Cary, NC, v9.4 and R Version 3.6.3.

RESULTS

Within age categories, 49% of participants from the Netherlands were aged ≥50 years, while 51% were <50 years. Mean age of Dutch participants was 48.6 (SD=11.3) years, higher than the remaining European countries (mean=43.0 years, SD=11.6, p=0.001). There was, however, no significant difference in mean duration of HIV (Netherlands, mean=12.8 years, SD=9.3 years, vs other European countries, mean=11.9 years, SD=10.3 years, p=0.524). Self-rated viral suppression was significantly higher among participants in the Netherlands (90.2%; 46/51) when compared to other European countries combined (77.1%; 708/918; p=0.029).

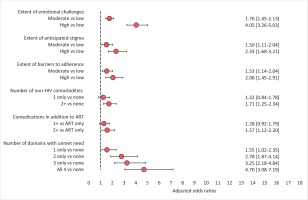

LAR preference, by unmet treatment need

LAR preference did not differ significantly between Dutch participants (58.8%; 30/51) versus other European countries (54.1%; 497/918; p=0.513). Country-specific prevalence estimates for LAR preference and various other perceptions towards HIV medications are shown in Figure 1. Overall, 32.2% of Dutch participants ranked LAR in first place of perceived importance out of seven treatment attributes assessed (Supplementary file Figure 1). In the pooled dataset across all 12 participating European countries, within each of the four domains of unmet need assessed (emotional, psychosocial/stigma, physical, adherence), LAR preference was higher among those reporting unmet need across a variety of indicators (Table 1). Not only were these individual indicators associated with LAR preference, within each domain, LAR preference generally increased with increasing number of challenges (Figure 2). However, LAR preference did not vary significantly within pooled analysis by age, gender, sexual orientation, domicile, or HIV duration.

Table 1

Prevalence of treatment dissatisfaction a and preference for non-daily ART regimens b between participants reporting or not reporting various ART-related challenges, Positive Perspectives Survey in the Netherlands and 11 other European countries combined, 2019 (N=969)

Burden of emotional challenges and associations with LAR preference

Of Dutch participants, 3.9% (2/51) were stressed by taking their HIV medications daily, 9.8% (5/51) associated daily dosing with bad memories, 11.8% (6/51) felt daily oral dosing limited their life, and 35.3% (18/51) said taking HIV medications daily reminded them of their HIV. Furthermore, 27.5% (14/51) perceived that HIV had an overall negative impact on their life.

Of the various indicators for ART-related emotional challenges assessed in the pooled analysis, those associated with the greatest LAR preference were the perception that daily oral dosing limited their life [74.6% (179/240) vs 47.7% (348/729) among those with vs without this perception, respectively, PD=26.9 percentage points] and perceived stress from their daily oral dosing schedule [71.6% (207/289) vs 47.1% (320/680), PD=24.5 percentage points].

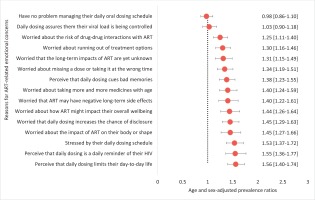

After adjusting for age and gender within the pooled dataset, a report of emotional challenges with current daily ART was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of preferring LAR. For example, the likelihood of indicating a preference for LAR was significantly higher among those reporting versus not reporting the following limitations: perceived stress from their daily oral dosing schedule (adjusted prevalence ratio, APR=1.53), perception that daily oral dosing is a daily reminder of HIV (APR=1.55), and the perception that daily oral dosing limits their life (APR=1.56) (all p<0.05). Other associations are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Relationship between reasons for ART-related emotional challenges and LAR preference among people living with HIV in 12 European countries, 2019 (N=969)

Using the number of ART-related issues over which participants expressed concerns as a proxy for the extent of emotional challenges, we found that the odds of preferring LAR increased with the extent of emotional challenges (tertiles). LAR preference odds were 1.76 and 4.05 higher among those with moderate and high levels of ART-related emotional burden, respectively, versus low (all p<0.05, Figure 2).

Burden of psychosocial challenges and associations with LAR preference

Of Dutch participants, 23.5% (12/51) had ever disguised their HIV medication in the past 6 months to avoid disclosing their HIV status, and of these, and 41.7% (5/12) indicated they would be very anxious if someone were to see their HIV medication. Although 35.3% (18/51) indicated they were comfortable sharing their HIV status, only 13.7% (7/51) reported they ‘always’ shared their HIV status. Furthermore, 9.8% (5/51) were concerned that taking HIV medicines every day increased the chances of someone knowing their HIV status. Also, 5.9% (3/51) of Dutch participants missed at least one ART dose in the past month because they were in a setting where they felt others could see them. Yet, discussing privacy concerns with providers was deemed uncomfortable by 2 in 5 participants in the Netherlands (41.2%; 21/51). Hesitancy in sharing HIV status was not only directed at distant acquaintances and casual relationships, but even at household members, sexual partners, and close friends, among those within those specified relationships. For example, 25.7% (9/35) reported not sharing their HIV status with their non-spousal sexual partners among those in such a relationship; 9.8% (5/51) had not shared with their siblings, parents, or children; and 6.1% (3/49) of those reporting close friendships had not shared with their close friends. More so, 37.8% (14/37) of those who worked had not shared with their co-workers. In relation to anticipated stigma, Dutch participants were more worried about the potential impact of disclosure on their interpersonal social relationships versus being worried about their personal health/safety from victimization because of their HIV status. For example, 39.2% (20/51) reported not sharing their HIV status at least once in the past because they were afraid it might affect their friendships, and 41.2% (21/51) because it might affect their romantic relationships (Supplemental file Figure 2). In contrast, only 7.8% (4/51) and 3.9% (2/51) reported ever withholding their HIV status because they were afraid for their safety, or because they were afraid of being prosecuted on account of their HIV status, respectively (Supplementary file Figure 2).

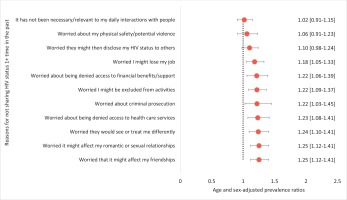

In pooled multivariable analysis, refusing to share HIV status for reasons not related to anticipated discrimination (e.g. simply because their HIV status was not relevant to the discussion), was not associated with LAR preference (Figure 4). However, refusing to share HIV status for reasons related to anticipated discrimination was generally associated with LAR preference. For example, LAR preference was significantly higher among those who refused to share their HIV status for fear of losing their jobs (APR=1.18), being denied financial benefits (APR=1.22), being denied healthcare services (APR=1.23), being seen differently (APR=1.24), damaging their romantic relationships (APR=1.25), or losing their friendships (APR=1.25) (all p<0.05).

Figure 4

Relationship between reasons for anticipated stigma and LAR preference among people living with HIV in 12 European countries, 2019 (N=969)

Using the number of reasons reported for nondisclosure of HIV status as a proxy for extent of anticipated stigma, we found that the odds of preferring LAR increased with extent of anticipated stigma (tertiles). LAR preference odds were 1.50 and 2.33 among those with moderate and high levels of anticipated stigma, respectively, versus low (all p<0.05, Figure 2).

Burden of adherence challenges and associations with LAR preference

Of Dutch participants, 37.2% (19/51) reported missing ART 1+ time in the past month for any reason, while 13.7% (7/51) reported adherence anxiety (i.e. being worried about forgetting to take their daily oral ART as prescribed). The leading contributors to missing ART were non-medical reasons (e.g. lifestyle related factors). Of those who missed ART at least once in the past month for any reason, 94.7% (18/19) reported a non-medical reason, including travel, privacy concerns, being busy with recreational activities, using recreational drugs, bored, wishing to forget about HIV, or not having their pills with them when they were supposed to dose.

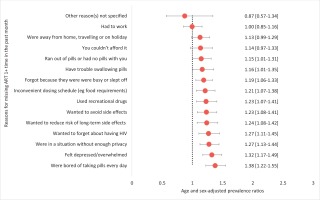

In pooled bivariate analysis, those reporting adherence anxiety had significantly higher LAR preference than those without adherence anxiety [63.3% (255/403) vs 48.1% (272/566), p=0.008]. Reasons for missing ART that were associated with LAR preference fell into themes of emotional challenges (e.g. bored of taking medicines every day, APR=1.38; depressed, APR=1.32; or wanting to forget about HIV, APR=1.27); lifestyle-related factors (using recreational drugs, APR=1.23; being busy, APR=1.19; or not having their pills with them, APR=1.15), as well as physical effects or challenges (side effects, APR=1.23; or difficulty swallowing pills, APR=1.16) (all p<0.05, Figure 5).

Figure 5

Relationship between reasons for missing ART at least once in the past month and LAR preference among people living with HIV in 12 European countries, 2019 (N=969)

Using the number of reasons reported for missing at least one ART dose in the past month as a proxy for extent of adherence challenges, we found that the odds of preferring LAR increased with extent of adherence challenges. LAR preference odds were 1.53 and 2.06 among those with moderate and high levels of adherence barriers, respectively, versus low (all p<0.05).

Burden of comorbidities and other physical limitations and their associations with LAR preference

Of Dutch participants, 84.3% (43/51) reported being ever diagnosed of at least one non-HIV comorbidity, and 39.2% (20/51) reported polypharmacy. Overall, 13.7% (7/51) reported each of the following: ever diagnosed with a gastrointestinal disease (e.g. Crohn’s disease), worried their ART would cause drug-drug interactions with other medications, and difficulty swallowing pills. Other conditions ever diagnosed of were liver disease (17.6%; 9/51), neurological disorders (19.6%; 10/51), and mental health disorders (37.3%; 19/51). Overall, 31.4% (16/51) reported side effects from their current ART, and of these, 68.7% (11/16) experienced gastrointestinal symptoms.

In pooled bivariate analysis, individuals with difficulty swallowing pills reported higher LAR preference than those without difficulty swallowing pills [56.9% (140/246) vs 53.5% (387/723), p<0.001]. They also reported higher dissatisfaction with their treatment (Table 1). After adjusting for age and gender, both the type and number of comorbidities reported were associated with LAR preference. LAR preference was significantly higher among those ever versus never diagnosed of a gastrointestinal disease (e.g. Crohn’s disease, APR=1.19; 95% CI: 1.02–1.38), bone disease (APR=1; 95% CI: 1.01–1.41), lipodystrophy (APR=1.23; 95% CI: 1.04–1.43), mental health disorders (APR=1.26; 95% CI: 1.11–1.43), substance use disorder (APR=1.28; 95% CI: 1.10–1.50), and malabsorption (APR=1.37; 95% CI: 1.04–1.79) (all p<0.05, Supplemental file Figure 3). The number of conditions, LAR preference odds were 1.71 higher among PLHIV with 2+ non-HIV comorbidities versus HIV only, and 1.57 higher among those on 2+ co-medications versus ART exclusively (all p<0.05).

Unmet needs in multiple domains and the association with LAR preference

People can have unmet needs across the different domains, which can impact LAR preference. Within pooled multivariable analysis adjusting for age and gender, LAR preference odds were 1.55, 2.78, 3.25, and 4.70 among those with substantial unmet need on one, two, three, or all four domains, respectively, versus none (Figure 2).

Decomposition analysis of the gap in LAR preference between those with versus without the perception that their ART needs improvement

Our analyses revealed that how people felt about their HIV medicines was associated with how they felt about living with HIV in general and with their preference for LAR. Participants who perceived room for improvement with their HIV medicines were more likely to perceive that living with HIV had a negative impact on their lives (50.9%; 173/340) compared to those not perceiving room for improvement with their ART (32.4%; 204/629) – a gap of 18.5 percentage points. Those with perceived room for ART improvement also had significantly higher prevalence for LAR preference (20.4 percentage points higher) when compared to those without perceived room for ART improvement [67.6% (230/340) vs 47.2% (297/629)] (all p<0.05).

Differences in ART-related emotional challenges (with higher prevalence among those with vs without perceived room for ART improvement) accounted for a substantial part of the gaps in health outcomes observed, explaining 70.6% of the gap in negative sentiments about living with HIV, and 59.4% of the gap in LAR preference (Table 2). Furthermore, higher anticipated stigma among those with perceived room for ART improvements explained 47.6% of the gap in negative sentiments about living with HIV, and 20.4% of the gap in LAR preference. Greater adherence challenges among those with versus without perceived room for ART improvement further explained 19.8% of the gap in negative HIV sentiments, and 16.5% of the gap in LAR preference. Differences in health conditions/physical limitations, including comorbidities, co-medications, difficulty swallowing pills, and self-reported viral suppression explained 18.6% of the gap in negative sentiments about HIV, but only 7.3% of the gap in LAR preference. Notably, self-reported viral status did not independently explain, to any significant extent, the observed gaps for either outcome. Likewise, differences in sociodemographic characteristics and HIV duration did not explain, to any significant extent, the differences seen between those with versus without perceived room for ART improvement for either outcome.

Table 2

Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition analysis explaining what factors account for the higher prevalence of the indicated outcomes among those perceiving room for improvement with their ART compared to those without this perception in the Netherlands and 11 other European countries combined, 2019 (N=969)

| Explanatory variables | Outcome Perception that HIV has a negative impact on their overall life | Outcome Preference for non-daily regimens | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of gap in outcome explained between those with vs without perceived room for ART improvement | p | Percent of gap in outcome explained between those with vs without perceived room for ART improvement | p | |

| Emotional challenges | ||||

| Worried about drug-drug interactions | 13.1 | 0.020 | 8.5 | 0.017 |

| Worried about ART impacting their overall well-being | 30.7 | <0.001 | 17.8 | <0.001 |

| Worried about long-term ART side effects | 27.5 | <0.001 | 14.2 | 0.005 |

| Stressed by their daily ART dosing schedule | 34.8 | 0.002 | 23.6 | <0.001 |

| Perceive that daily ART dosing limits their life | 24.2 | 0.001 | 22.9 | <0.001 |

| Perceive that daily ART dosing cues bad memories | 29.5 | <0.001 | 13.9 | <0.001 |

| Perceive that daily ART dosing reminds them of HIV | 25.8 | <0.001 | 18.0 | 0.004 |

| Worried about taking more and more medicines with age | 18.6 | 0.002 | 14.5 | <0.001 |

| All emotional factors above | 70.6 | <0.001 | 48.1 | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial/anticipated stigma | ||||

| Pill-induced anticipated stigmaa | 35.2 | 0.001 | 18.9 | <0.001 |

| Inter-personal anticipated stigmab | 32.4 | <0.001 | 10.7 | 0.056 |

| Any form of anticipated stigma | 47.6 | <0.001 | 20.4 | <0.001 |

| Adherence challenges | ||||

| Adherence anxietyc | 11.2 | 0.022 | 8.7 | 0.002 |

| Poor adherence behaviord | 10.8 | 0.084 | 10.5 | 0.058 |

| Any form of adherence challenge | 19.8 | 0.009 | 16.5 | 0.003 |

| Physical challenges | ||||

| Difficulty swallowing pills | 3.6 | 0.138 | 0.6 | 0.677 |

| Comorbidities ever diagnosed | 8.6 | 0.009 | 2.1 | 0.168 |

| Concomitant medications | 6.0 | 0.065 | 0.7 | 0.688 |

| Viral suppression | 3.9 | 0.180 | 4.0 | 0.230 |

| All physical factors above | 18.6 | 0.001 | 7.3 | 0.015 |

| All four categories of factors above (emotional, psychosocial, adherence, and physical) | 91.6 | <0.001 | 47.6 | 0.001 |

| Other demographic and contextual factors | ||||

| Age, gender, and HIV duration | 0.2 | 0.936 | 1.9 | 0.299 |

| HIV health literacye | 5.4 | 0.199 | 1.5 | 0.609 |

| Provider engagementf | 8.6 | 0.038 | 1.3 | 0.582 |

a A report indicating that the participant perceived their HIV medication as a potential physical cue for stigma by others. Affirmative responses (‘Agree’/‘Strongly agree’) to the following questions asking whether participants would be anxious or stressed: ‘if someone you did not want to see your HIV pills were to find them’; ‘if in the past 6 months, you had ever hidden or disguised your HIV medication to avoid revealing your status?’; and ‘if you worried that having to take pills every day means a greater chance of revealing my HIV status to others’.

b Reported reasons for which participants ever refused to share their HIV status because of anxiety over the prospect of any of the following happening simply because of their HIV status: ‘criminal prosecution’, ‘being denied access to financial benefits/support’, ‘my physical safety/potential violence’, ‘being denied access to health care services’, ‘it might affect my friendships’, ‘I might lose my job’, ‘it might affect my romantic or sexual relationships’, ‘I might be excluded from activities’, ‘they would see or treat me differently’, and ‘they might then disclose my HIV status to others’.

c Response of ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ to the statement: ‘I worry about forgetting to take my daily HIV medication or taking it later than planned’.

e Affirmative responses to the statements: ‘Pills for HIV can contain more than one type of medicine inside them. Do you know how many different HIV medicines you currently take each day?’; and ‘I feel I understand enough about my HIV treatment’.

f Assessed with the following indicators: ‘My provider seeks my views about treatment before prescribing an HIV medication’, ‘My provider asks me if I have any concerns about the HIV medication I am currently taking’; ‘My provider tells me about new HIV treatment options that become available’; ‘My provider asks me frequently about any side effects I might be experiencing with my HIV treatment’, and ‘When it comes to the management of my HIV treatment, I feel my main HIV care provider meets my personal needs and takes into account the things that are most important to me’

DISCUSSION

Daily dosing of antiretroviral treatments (ART) was associated with unmet needs among PLHIV, including conditions interfering with intake, suboptimal adherence, confidentiality concerns, and various emotional challenges13. Participants with unmet treatment needs were more likely not to report optimal health parameters. Indeed, the same factors that explained higher preference for LAR also explained higher prevalence of the sentiment that living with HIV was overall negative. Given that these challenges can deter PLHIV from starting or staying on treatment, addressing them is critical to meeting the 2030 targets of eradicating HIV/AIDS as a public health emergency.

Only 67.3% of PLHIV in a recent study agreed that their ‘main HIV care provider meets their personal needs and takes into account the things that are most important to them’18. Yet, addressing the preferences of PLHIV is central to person-centered care19. In our study, preference for LAR was strongly driven by quality-of-life (QoL) factors and not necessarily viral suppression. This is supported by the observation that PLHIV in the Netherlands, while having significantly higher prevalence of self-reported viral suppression compared to the rest of Europe, did not differ significantly in their LAR preference. Also, the difference in viral suppression between those with versus without perceived room for improvement with their ART was not a significant explanatory variable for the gap in LAR preference. In contrast, emotional-related challenges comprised the most important set of explanatory variables, together accounting for close to half of the gap in LAR preference between those with versus without perceived room for improvement with their ART. Taken together, these findings underscore the need for providers to consider patients’ quality of life and not just viral load, when making treatment decisions as recommended in the proposed ‘fourth 90’ target19.

Similar to our study, previous research shows that the preference for LAR can result from many different reasons6,20. Given that the key determinants of LAR preference in our study were psychographic rather than demographic factors, quality communication is necessary for providers to identify those patients with unmet needs and assist them with tailored care, including LAR where appropriate.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths include the use of a standardized instrument to assess treatment challenges and preferences among PLHIV in diverse settings. The data are relatively recent and offer insights on important issues at the intersection between emerging HIV treatments and patients’ preferences. Nonetheless, this study has some limitations. First, these are cross-sectional analyses and only associations can be drawn. Second, the data may not be fully representative of the individual countries or the European region, because sampling was done non-probabilistically and only a limited number of countries were included. The small number of participants from the Netherlands limited the ability to perform subgroup analyses. More so, the web-based survey may have systematically included more PLHIV of higher socioeconomic status. Finally, intentions (e.g. LAR preference) may not necessarily translate into actual behavior.

CONCLUSIONS

Even in countries such as the Netherlands where the UNAIDS 90–90–90 goals have been surpassed, unmet treatment needs exist in relation to HIV care. Some PLHIV had unmet needs related to daily oral dosing, including conditions that limit oral administration, emotional challenges, as well as privacy and confidentiality concerns. Furthermore, many PLHIV reported being worried about missing their ART doses or saw their pills as a daily reminder of HIV. New therapies such as LAR could help address some of these identified treatment needs and most participants in our study indicated preference for LAR. One-third of participants from the Netherlands ranked LAR as the single most important improvement to HIV medicines, higher than participants from other European countries. PLHIV’s preference for LAR was linked with a variety of reasons other than clinical indications, including lifestyle and QoL-related factors. The more unmet needs that existed and the more domains with unmet needs, the higher was the observed preference for LAR. It is important for healthcare providers to discuss the option of LAR with PLHIV, because without such conversations, providers are unlikely to be aware of patients’ unique circumstances, preferences, and personal lifestyles that might make LAR appealing and suitable.