INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 respiratory infection pandemic has rapidly evolved into a global public health threat. By the 31 March 2020, about 0.78 million COVID-19 cases had been reported in over 190 countries, including 37272 deaths1. The acceleration of transmission is demonstrated by the fact that, while it took over three months for the number of confirmed cases to reach 10000, in only 12 days the next 100000 confirmed cases had already been reported2.

With the aim of minimizing transmission and the subsequent burden of COVID-19 to the healthcare system, countries have dedicated significant resources to preparedness and response strategies3. Governments have applied a series of predominantly non-pharmaceutical measures. These measures include the practice of personal protective measures (hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, face masks), environmental measures (surface and object cleaning), social distancing (self-isolation, quarantine, school closures, workplace measures and closures), travel-related measures (travel advice, entry and exit screening, internal travel restrictions, border closures) as well as strategic risk communication and community engagement4.

The efficacy and impact of the aforementioned strategies are highly dependent on community compliance and cooperation5. Encouraging and motivating people to comply with specific behaviors regarding hygiene and social distancing has previously proven effective in mitigating other infectious disease outbreaks6,7. Nevertheless, the adoption of such behaviors depends on many factors related to personal perceptions and beliefs about the effectiveness of the precautionary measures, the perceived risk of contracting the disease or having friends/family being affected by the disease, the perceived severity of the health, economic and educational consequences8-11.

A better understanding of people’s behaviors, beliefs, concerns, knowledge, as well as of the associated predictive factors, during an emerging pandemic is of crucial importance for public health officials and decisionmakers, to enhance communication efforts for the promotion of individual and community health. Additionally, the cross-country exploration of differences in emergency preparedness and response strategies to a pandemic could provide useful information to identify effective approaches within the context of each country.

In light of the above and of the scarcity of relevant data for COVID-19, especially in the form of a cross-country comparison, this study aims to evaluate the public’s perceptions and practice of personal protective measures and social distancing to prevent COVID-19 transmission across the G7 nations (Canada, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United States) in late March 2020.

METHODS

Anonymous data were collected by the quota sampling method by the Public Division of Kantar between 19–21 March 2020, across all G7 countries: Canada, France, Great Britain (GB), Germany, Italy, Japan, and the US. Around 1000 online panelists, aged >18 years, responded per country, leading to a pooled sample size of 7005. Collected data were post-stratified with respect to gender by age group, and gender by degree-holding status within each country and were weighted using the US Census Bureau and education statistics from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to match population distributions for each of the G7 countries. All participants provided written informed consent to voluntarily participate in the study in which the data were fully anonymized. The current study was exempt from an ethics review by an institutional review board (IRB), as it was a secondary analysis of de-identified data.

Measures

The practice of protective behaviors

Protective behaviors were assessed by asking respondents: ‘Some people are able to make changes to their lifestyle in response to the coronavirus outbreak. Since the start of the outbreak, have you started doing any the following?’. Respondents selected all that applied from ten provided items. Three aggregate categories were created: 1) personal protective measure (washing hands, using hand sanitizers, wearing a mask); 2) social distancing (working from home, self-isolating at home, avoiding non-essential social contact, avoiding handshakes/keeping a distance, avoiding public transportation, avoiding visits to the elderly and vulnerable relatives/friends, and avoiding visits to pubs/cafes/restaurants); and 3) both personal protective and social distancing measures.

Concerns about the impact of COVID-19 on health, income and education

Concern about health was assessed using three questions that asked how much respondents were concerned about their health, the health of family and friends, and other people living in their country. Concern about community health was assessed using three questions, which asked how much respondents were concerned about health and wellbeing of their neighbors/community, availability of local health services, and local social care services for the elderly and vulnerable. Responses were dichotomized as concerned (very/fairly concerned) and not concerned (not very/not at all concerned, don’t know).

Concern about income was assessed using two questions asking about respondents’ personal income and household income. Respondents were classified as concerned if they answered: ‘Coronavirus has already impacted on my personal/household income’ or ‘Coronavirus has not yet impacted on my personal/household income, but I expect it to do so in the future’ (vs not concerned, i.e. ‘Coronavirus will have no impact on my personal/household income’ or ‘Don't know’).

Concern about education was assessed with the question: ‘If this is applicable to you, how concerned are you about either your own education or the education of your children?’. Respondents were classified as ‘concerned (very/fairly concerned)’, ‘not concerned’ (not very/not at all concerned or don’t know), or not applicable.

Perceptions regarding precautionary measures and COVID-19

Perceived effectiveness of preventive measures was assessed using nine items: asking people to stay home, closing schools, closing colleges/universities, closing the country borders, shutting down public transport, closing public places, isolating older people, social distancing, and setting restrictions on movement outside the home. An index was created by summing up the number of items for which respondents provided an affirmative response (very/fairly effective vs not very/not at all effective or don’t know). The index score was classified into low (0–3), moderate (4–6), and high (7–9). Perceived spread of COVID-19 was assessed by whether respondents themselves and/or their close family members/friends have contracted the virus. Responses were dichotomized into yes (‘Yes, definitely’, ‘Yes, I think so’, or ‘Possibly’) and no (‘No’, ‘Don't know’).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the G7 countries overall and by country with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Chi-squared tests were used to examine within- and across-group differences with statistical significance set at p<0.05. To investigate predictors of protective behaviors, multivariable logistic regression models were fitted separately for each of the three variables of protective behaviors (personal protective measures, social distancing, and both of these). Independent variables included in the models were selected from the variables that were associated with protective behaviors at the bivariate level, with the exception of the measure of concern about community health, which was not included in the final models as it was highly correlated with concern about health (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.58). All analyses were conducted in late March 2020, using R version 3.6.2.

RESULTS

Concerns about the impact of COVID-19 on health, income and education

Table 1 shows the percentages of reported concerns about the impact of COVID-19 stratified by country and gender across the G7 countries. Overall, 90.8% of respondents reported any type of concern with regard to the impact of COVID-19 on health including their own health, the health of their families and friends, and the health of other people living in their country. In all, 89.1% of respondents reported any type of concern about the health and wellbeing of neighbors and community, availability of local health services and local social care services for the elderly and the vulnerable. In GB, Germany and the US, a higher percentage of females than males reported any concern about the impact of COVID-19 on local community’s health and wellbeing, and the availability of services (p<0.05). Overall, 75.2% of respondents reported that COVID-19 had or is expected to impact their personal or household income (from 60.7% in Germany to 87.9% in Italy), and 41.7% reported concerns about the impact on their own or their children’s education (from 31.5% in Germany to 44.3% in the US).

Table 1

Levels of concern about health, community, finances and education, overall and by G7 country and gender, late March 2020

Practice of protective behaviors

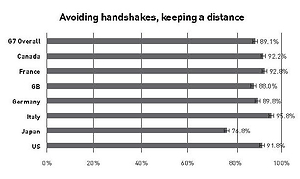

Table 2 presents percentages of the practice of protective behaviors to prevent COVID-19 transmission by sociodemographic characteristics and relevant perceptions in G7 countries. Overall, 85.4% of respondents reported practicing personal protective measures, 91.2% reported taking social distancing measures, and 81% reported taking both personal protective measures and social distancing measures. The most frequently reported personal protective measure was washing hands more often/for longer (76.5%), followed by the use of hand sanitizing gel (53.9%), and, to a lesser extent, the use of a mask (26.0%). Among the social distancing measures, avoiding handshakes and keeping at a distance was most common (89.1%). A smaller percentage reported working from home (28.7%).

Table 2

Practice of protective behaviors to prevent COVID-19 transmission, by sociodemographic characteristics, relevant concerns and perceptions in G7 countries, late March 2020

The practice of personal protective measures and social distancing measures is displayed by country in Figure 1. Country-specific breakdown by sociodemographics is presented in the Supplementary file (Table S1 for EU Countries and Table S2 for non-EU countries).

Figure 1

The use of both personal protective and social distancing measures bycountry,lateMarch2020 (N=7005)

The practice of protective behaviors differed across sociodemographic groups. For the practice of both personal protective measures and social distancing, the percentage was higher in Italy (91.8%), Canada (90.8%) and France (86.8%), and lower in Japan (61.8%). The reported practice of both protective behaviors was higher among females (85.8%) than males (77.1%), older adults aged ≥65 years (86.5%) than young adults aged 16–24 years (74.7%), and those with a college/university degree (86.0%) than those without any full-time education (72.5%). By type of most trusted source of information, the percentage of practicing both protective behaviors was higher among those who reported doctors/healthcare providers (89.1%), followed by government/politicians (88.1%). Lower percentages were seen for those who reported social media as their trusted source of information (78.3%) (all p<0.05).

Associations between concerns/perceptions towards the COVID-19 outbreak and practice of protective behaviors

Table 3 presents the associations between concerns and perceptions towards the COVID-19 outbreak and the practice of protective behaviors across the G7 nations. At the time of the survey, respondents from GB, Germany, Japan and the US, were less likely than respondents in Italy to practice personal protective behaviors and social distancing measures.

Table 3

Associations between sociodemographic characteristics, concerns and perceptions and the practice of protective behaviors to prevent COVID-19 transmission in G7 countries, late March 2020 (N=7005)

Males were less likely than females to practice both personal protective measures (AOR=0.60; 95% CI: 0.48–0.79) and social distancing measures (AOR=0.59; 95% CI: 0.45–0.79), while those with lower education were less likely to practice protective behaviors (AOR=0.63; 95% CI: 0.43–0.89), social distancing (AOR=0.45; 95% CI: 0.27–0.75), and both approaches (AOR=0.54; 95% CI: 0.37–0.77). Older age was also positively associated with practicing social distancing, although a significant association was not observed between age and personal protective measures. The highest odds of practicing social distancing were observed among older adults ≥65 years (AOR=3.09; 95% CI: 1.61–5.96), followed by those aged 45–64 years (AOR=2.14; 95% CI: 1.16–3.96) and those aged 25–44 years (AOR=1.99; 95% CI: 1.11–3.56) compared to those 16–24 years of age. Moreover, older adults aged ≥65 years were more likely to practice both personal protective measures and social distancing (AOR=2.08; 95% CI: 1.32–3.26) compared to those aged 16–24 years.

Respondents who expressed concern about the impact of COVID-19 on their health or the health of their family, friends and people in their country had nearly three times higher odds of practicing personal protective measures (AOR=2.81; 95% CI: 2.02–3.93) and social distancing (AOR=3.18; 95% CI: 2.21–4.56). Similarly, those who were concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on their own or their children’s education were more likely to practice personal protective measures (AOR=1.74; 95% CI: 1.32–2.28) and social distancing (AOR=1.68; 95% CI: 1.15–2.45). Moreover, respondents who were concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on their income were more likely to practice protective behaviors (AOR=1.54, 1.89, and 1.65 for personal protective measures, social distancing, or both, respectively).

Perceived effectiveness of precautionary measures was also associated with the practice of protective behaviors: the odds of practicing social distancing were 3.99 (95% CI: 2.69–5.92) times higher among those who had a high level of perceived effectiveness compared to those with a low level of perceived effectiveness. Respondents who reported that they or a close family member/friend had contracted COVID-19 had a lower likelihood of practicing personal protective measures and practicing both approaches (AOR=0.57 in both cases). Finally, compared to respondents who reported doctors or healthcare providers as their most trusted source of information, those who reported any other type of information source (with the exception of government/politicians) were significantly less likely to practice both protective behaviors.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies to assess public perceptions and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic using data from seven countries. Among G7 countries, over 75% of respondents reported washing hands more often/for longer since the start of the outbreak. While slightly different measures, this compares to the Wang et al.12 (2020) study in which in the past 14 days, 66.6% reported always washing hands after touching contaminated objects. In both studies, among all protective measures, washing hands was the most frequently reported, which may be a result of the emphasis placed by the World Health Organization on handwashing as the official guidance for how to protect yourself from COVID-1912. Almost all Ministries of Health have also published guidelines on how to wash hands properly. Hand-washing is also the easiest measure to practice, while sanitizing products and masks are more dependent on product availability.

With regard to masks, at the time of the survey there was controversy on whether they should be worn by the general public, and personal discomfort and sense of embarrassment could also affect compliance13. In the present study, handwashing was more commonly practiced than wearing a mask in all G7 countries except Japan, where wearing a mask was more frequently reported (65%) than washing hands (56%). It is reasonable that Japan had the highest percentage of reported mask use given that it is a common practice in Japan for the prevention of sickness and as general etiquette. After Japan, Italy also had 2.3–5.4 times higher reported mask use (62%, just slightly lower than Japan) than other G7 countries. This could be explained by differences in the stage of the outbreak at the time of data collection in each of the G7 countries, demonstrated by the varied numbers of confirmed cases and fatalities. For instance, during the fieldwork dates, the number of cases in Italy had reached 53578, while less than half that number had been reported in Germany (22364 cases)14. Other possible explanations include differences in governmental responses to the outbreak, risk communication messages and guidelines on personal protective measures across countries.

Concern about COVID-19 was a strong predictor of practicing protective behaviors regardless of the type of behavior (personal protective measures or social distancing). Of the three aspects assessed (health, income, and education), concern about health showed the strongest association. On average, 82% of respondents reported being concerned about the health of family and friends. These results compare to a population-based survey in China by Wang et al.12 (2020), in which 75.2% of respondents reported being very or somewhat worried about family members getting COVID-19. Notably, in our study, more respondents were concerned about the health and wellbeing of other people living in their country and their local communities than for their own health. This suggests that focus should be placed on conveying how protective measures are vital to safeguarding the health and wellbeing of others.

Our findings revealed a significant association between perceived effectiveness of precautionary measures and practicing protective measures. It is critical to inform the public of the purposes and expected effects of recommended preventive measures to keep them in compliance and to promote personal protective behaviors. Furthermore, compared to other information sources, people who most trusted doctors/healthcare providers and government/politicians were more likely to practice protective behaviors, highlighting the importance of their roles in health communication. Consistent with previous findings15,16, our study revealed disparities in protective behaviors as demonstrated by the lower practice among males, young people, and those with less education. Health communication strategies should utilize data and various channels to maximize the reach of the messages. Attention should also be made to message framing to avoid confusion and engage all populations, including those with lower health literacy and the vulnerable17.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, by using online access panels as the sample source, where people self-select onto these panels, there is the possibility of residual bias not addressed by post-stratification and weighting. Second, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we cannot establish causal relationships. Finally, we were unable to consider any possible effects of ecological factors that could strongly predict people’s behaviors (e.g. differences in social damages from the COVID-19 pandemic, instructions or laws adopted in each country, cultural differences, social norms).

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings detail the picture of the perceptions and practice of personal protective behaviors across the G7 nations during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of respondents were concerned about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health, income, and education, with respondents who expressed these concerns more likely to practice protective measures. Personal behaviors to prevent and reduce the spread of the virus are the frontline measures to control this pandemic. Hence, population-wide interventions should focus on ensuring increased adherence and tailoring health-related communications to groups that are less likely to practice protective measures.