INTRODUCTION

As people living with HIV (PLHIV) grow older, develop more comorbidities, and receive more medications, their risk of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) increases1,2. Polypharmacy and the associated risk of DDIs is higher among but not restricted to older adults; 54.6% of older adults living with HIV in a recent international study reported polypharmacy, but so did 36.5% of those aged <50 years3. Not all DDIs result in a toxic, noxious, or otherwise observable adverse clinical effect4, but when they do, it can be severe enough to disrupt care and overall quality of life5. In a survey of 688 PLHIV in Western Europe, 23.9% indicated that ‘I cannot take antacids, proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers to relieve stomach issues along with my HIV treatment’, and 16.1%, reported ‘I cannot take another drug at the same time as my HIV treatment’5. Also, 19.1% reported they needed monitoring when taking other medications with ART while 15.4% had ever changed ART because of DDIs. Results from the Swiss HIV Cohort study of 1497 ART-treated patients found that 68% had a co-medication and 40% had a potential DDI2. In this cohort, 2% of patients with co-medications had red-flag interactions (contraindicated) while 59% had orange-flag interactions (potential dose adjustment and/or close monitoring needed).

Addressing DDIs is central to the concept of person-centered care which shifts focus from the patient to the person, encouraging providers to look beyond the presenting complaint of their patient and to consider the person holistically – medically, psychosocially, and emotionally6. PLHIV should never have to be in a situation where they are forced by DDIs to choose which medication to take over the other, yet 10.5% of PLHIV who missed ART in a recent study reported doing so because their ART interacted with other medications they were taking5. The basis for concern about such DDI-induced non-adherence is that failing to take HIV medicines as prescribed, including the proper dose, time, and under the right conditions, can lead to the emergence of drug resistance, treatment failure and disease progression. Reducing DDIs is therefore paramount if the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets of starting and keeping people on ART (second target), as well as achieving and maintaining viral suppression (third target) are to be met7. Reducing DDIs is also critical to the proposed newer targets aimed at achieving good quality of life and accessing person-centered care among PLHIV8.

While studies have extensively examined the clinical and pharmacokinetic correlates of DDIs with ART2,4,9-11, less is known about DDIs from the perspective of PLHIV, including their concerns and how these may have evolved over time; the impact of DDIs on quality of life; or how DDIs play a role in treatment choices among PLHIV. To fill these knowledge gaps, we analyzed pooled data from an international survey of PLHIV to explore three key questions: 1) what percentage of PLHIV have ever switched their HIV medication because of complications with other medications they are on?; 2) What are clinical, sociodemographic, and geographical factors associated with reported concerns about the risk of DDIs among PLHIV?; and 3) What are the associations between DDI experiences and health-related outcomes, including subjective evaluation of overall wellbeing and other indicators of quality of life?

METHODS

Data source

Data came from the international, web-based, cross-sectional study called ‘Positive Perspectives Wave 2’ that was conducted among adult PLHIV aged ≥18 years during 2019 (n=2389)3,12-16. Participants were recruited from Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, UK, and the USA. PLHIV were sampled non-probabilistically from existing panels of confirmed HIV sero-positive individuals, from national, regional, and local charities/support groups; and online support groups/communities and social media platforms. Surveys were translated into local languages. In the Asian region, 230 participants were recruited: China (n=50), Taiwan (n=55), Japan (n=75), and South Korea (n=50).

Measures

Ever switching of ART because of DDIs

Participants were asked whether they had ever changed their ART ‘to a different medication or combination of medications’, as well as the reasons for the change. Individuals who reported ever changing ART because ‘My HIV medicines did not work well with other medicines/drugs/pills I was taking’ were classified as reporting a past ‘major DDI’ with ART (i.e. experienced DDIs that were severe enough to warrant a complete switch of their ART). This is a very conservative construct as it likely captures only the manifestations of DDI that were severe enough to cause switching or modification of ART but not milder manifestations.

Current concerns, perceptions and treatment priorities

The survey assessed whether participants were currently concerned about DDIs, how their attitudes about DDIs had changed from when they first started HIV treatment versus now, the extent to which they prioritized issues related to DDI in their current treatment, and whether they were comfortable discussing DDI-related concerns with their healthcare providers.

Participants were classified as being currently concerned about the risk of DDIs if they responded ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ (vs ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, or ‘neither agree nor disagree’) to the statement ‘I worry how my HIV medicines will affect other medications/drugs/pills I take’. To evaluate how attitudes towards ART may have changed over time among treatment-experienced individuals (those diagnosed for ≥1 year), eligible participants responded to two separate items in the survey that asked them what they prioritized the most when they first started ART, and what their priorities were now at the time of the survey. Both items were completed within the same survey but based on the respondent’s recall of the different time periods in question. Based on these responses, reducing DDIs was considered a new treatment priority if it was not deemed important at ART initiation (based on the respondent’s recall) but was deemed important now. Conversely, reducing DDIs was considered a current treatment priority if it was deemed important now, regardless of participants’ recall of its perceived importance at ART initiation. Among all participants, perceived comfort discussing DDI-related concerns with their healthcare providers was assessed by asking participants to rate to what extent they would feel comfortable discussing with their main HIV care provider ‘concerns about how your HIV medication affects other medications/drugs/pills you take’. Those answering ‘comfortable’ or ‘very comfortable’ (vs ‘very uncomfortable’, ‘uncomfortable’, or ‘neither comfortable nor uncomfortable’) were classified as being comfortable discussing DDI-related issues with their healthcare providers.

Discrete choice experiment to rank PLHIV’s current treatment priorities

To better understand the perceived relative importance (from the perspective of PLHIV) of the need to reduce the number of medicines taken as well as DDIs within the context of other improvements to HIV medicines, a discrete choice experiment17 was performed as part of the survey. Participants ranked the following ART attributes in order of perceived importance: reduced DDIs, smaller pills, fewer side effects, reduced long-term negative impacts, no food requirements, less medicines each day but just as effective, and non-daily regimens. More details about this question item have been described elsewhere18.

Clinical parameters

From a list of 21 health conditions (including a catch-all ‘other’ category), participants were asked to select which conditions they had ever been diagnosed with, and which ones they were currently taking medicines for at the time of the survey. Assessed conditions were mental illness, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, insomnia, gastrointestinal disease (e.g. gastric ulcer), anemia, liver disease, arthritis, lung disease, substance use disorder, lipodystrophy, bone disease, diabetes, heart disease, neurological conditions, kidney disease, tuberculosis, malabsorption, and dementia. Each condition was recoded as a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ variable.

From these data, we created a tally of non-HIV conditions participants had ever been diagnosed with (range: from 0 for those living only with HIV, to ≥7 conditions), as well as conditions for which they were currently taking medicines at the time of the survey, including HIV (range: from 1 for those taking medicines only for HIV, to ≥7 conditions). Counts of comorbidities and concurrent treatments 7 or greater were collapsed as ‘≥7’ because of sample size considerations.

Self-reported virologic control was defined as a response of ‘undetectable’ or ‘suppressed’ versus ‘detectable,’ ‘unsuppressed,’ ‘I don't know,’ or ‘prefer not to say’ to the question: ‘What is your most recent viral load?’. Polypharmacy was defined as taking ≥5 pills per day for HIV or non-HIV conditions, or currently taking medicines for ≥5 conditions, including HIV3. Suboptimal adherence was defined as a report of one or more reasons for missing ART for ≥5 times within the past month12. Self-ratings of physical, mental, sexual, or overall health as ‘good/very good’ were classified as optimal health (vs ‘very poor/poor’/‘neither good nor poor’).

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates for DDI-related endpoints were stratified for participants in the Asian region versus other non-Asian geographical regions. All multivariable analyses were however performed on pooled data using the full dataset (n=2389) to increase sample size. Adjusted prevalence ratios were calculated in a multivariable Poisson regression model19 to explore factors associated with a past major DDI (coded as 1 if they ever switched ART because of DDIs, coded as 0 if they never switched ART, or switched for reasons other than DDIs). Secondary outcomes explored in the multivariable analysis were a report of DDIs as a current treatment priority, as well as a report of DDIs as a new treatment priority, as defined earlier. The independent variables assessed in the exploratory regression models were age, gender, geographical region, education level, domicile, HIV duration, number of concomitant medications, and ART formulation (i.e. single, or multi-tablet regimen). To examine how the types of current medical treatments for other non-HIV conditions were associated with participants’ concerns about their risk of ART-related DDIs, adjusted prevalence ratios were calculated for each co-treatment assessed, with perceived concern over DDI risk (yes or no) as the dependent variable, and condition-specific treatment status as the independent variable (coded as 1 if taking medication for the condition now, 0 if otherwise), adjusting for age, gender, and geographical region. Similarly, to examine how the type of non-HIV comorbidity ever diagnosed of was associated with participants’ past switching of HIV medication because of ART-related DDIs, adjusted prevalence ratios were calculated with DDI-induced past ART switching as the outcome (ever vs never), and ever diagnosis of the specified condition as the predictor (coded as 1 if ever diagnosed of the condition, 0 otherwise), adjusting for age, gender, and geographical region.

To measure the relationship between DDI experience/concerns (exposure variable) and various health-related outcomes, we classified the exposure variable into three categories: 1) reported neither a history of DDI-induced ART switching nor any concerns about DDI risks; 2) reported concerns about DDI risks but no history of DDI-induced ART switching; and 3) reported history of DDI-induced ART switching (i.e. past major DDI). Estimation of prevalence ratios within a Poisson regression model adjusted for age, gender, geographical region, and presence of non-HIV comorbidities; the last was included as a control variable to assess the independent effect of number of medications being administered (modifiable factor) separate from conditions ever diagnosed of (non-modifiable factor). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS, Cary, NC, v9.4 and R v3.4.

RESULTS

Of the 230 participants from the Asian region, 78.3% (180/230) were aged <50 years, 67.8% (156/230) self-reported as male, 83.9% (193/230) had greater than high school education level, 79.1% (182/230) had been diagnosed with HIV within the past decade (i.e. 2010–2019), 58.3% (134/230) lived in a metropolitan area, and 66.1% (152/230) reported being viral suppressed. Furthermore, 86.0% (43/50) of Asian participants aged ≥50 years reported having ever been diagnosed with a non-HIV comorbidity versus 60.0% (108/180) of those aged <50 years (p=0.001). Some of the conditions ever diagnosed based on self-report were mental illness (19.4%), hypertension (17.4%), hypercholesterolemia (16.0%), insomnia (15.0%), gastrointestinal disease (e.g. gastric ulcer, 12.2%), anemia (11.2%), liver disease (10.3%), arthritis (8.6%), lung disease (8.5%), substance use disorder (8.2%), lipodystrophy (8.2%), bone disease (6.7%), diabetes (6.3%), heart disease (6.2%), neurological conditions (5.7%), kidney disease (4.1%), tuberculosis (4.1%), malabsorption (1.8%), and dementia (1.1%).

DDI-related experiences and perceptions

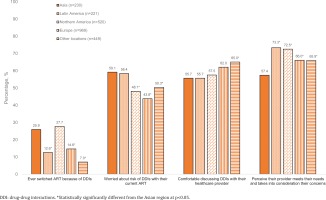

Of all participants from the Asian region, 59.1% (136/230) reported they were concerned about the risk of DDIs (China 56.0%, Japan 57.3%, South Korea 58.0%, Taiwan 65.4%), 58.3% (134/230) were concerned about having to take more medicines as they grew older (China 72.0%, Japan 42.7%, South Korea 64.0%, Taiwan 61.8%), and 25.9% (44/170) of those who had ever switched ART in the Asian region attributed it to DDIs (China 43.4%, Japan 23.4%, South Korea 20.7%, Taiwan 15.8%) (Table 1). Switching ART because of DDIs within the Asian sample was around two-fold higher among men who have sex with women [37.0% (20/54)] than men who have sex with men [15.8% (9/57), p=0.016]; those living in non-metropolitan [36.1% (26/72)] than in metropolitan areas [18.4% (18/98), p=0.011], and those on multi-tablet ART regimens [32.2% (38/118)] than on single-tablet regimens [12.0% (6/50), p=0.006]. When compared to several other geographical regions, participants in the Asian region were more likely to switch ART on account of DDIs, as shown in Figure 1. Only 55.7% (128/230) of Asian participants felt comfortable discussing DDIs with their healthcare providers (China 50.0%, Japan 72.0%, South Korea 26.0%, Taiwan 65.4%) (Figure 1). Furthermore, participants in the Asian region reported the lowest percentage (57.4%) of those who perceived that their healthcare provider met their needs and took into consideration the things important to them (Figure 1).

Table 1

Prevalence of various perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors related to drug-drug interactions among people living with HIV during 2019, by geographical region

| Characteristics | Asian region (n=230) | Non-Asian region (n=2159) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Worried about DDIsa | Worried about taking more and more medicinea | Comfortable discussing DDIs with providera | Ever changed ART because of DDIsb | n | Worried about DDIsa | Worried about taking more and more medicinea | Comfortable discussing DDIs with providera | Ever changed ART because of DDIsb | |

| Total | 230 | 59.1 | 58.3 | 55.7 | 25.9 | 2159 | 47.7 | 56.3 | 60.9 | 16.6 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| <50 | 180 | 61.7 | 61.1 | 55.6 | 25.4 | 1510 | 49.9 | 56.8 | 56.4 | 19.3 |

| ≥50 | 50 | 50.0 | 48.0 | 56.0 | 27.8 | 649 | 42.5 | 55.3 | 71.3 | 11.7 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 156 | 60.3 | 62.8 | 61.5 | 26.9 | 1467 | 46.0 | 54.9 | 63.1 | 16.4 |

| Female | 73 | 57.5 | 47.9 | 42.5 | 22.0 | 623 | 50.6 | 59.4 | 57.8 | 17.4 |

| Binary/other | 1 | ¶ | ¶ | ¶ | ¶ | 69 | 56.5 | 59.4 | 42 | 10.7 |

| Education level | ||||||||||

| High school or less | 35 | 54.3 | 45.7 | 51.4 | 40.0 | 497 | 43.7 | 54.9 | 58.4 | 14.0 |

| >High school | 193 | 60.1 | 60.6 | 57.0 | 23.4 | 1563 | 48.2 | 56.0 | 63.5 | 17.3 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | ¶ | ¶ | ¶ | ¶ | 99 | 59.6 | 67.7 | 32.3 | 15.4 |

| Domicile | ||||||||||

| Metropolitan | 134 | 56.0 | 57.5 | 59.7 | 18.4 | 1201 | 49.0 | 58.1 | 64.4 | 14.3 |

| Non-metropolitan | 96 | 63.5 | 59.4 | 50.0 | 36.1 | 958 | 45.9 | 54.1 | 56.5 | 19.7 |

| HIV diagnosis year | ||||||||||

| 2017 to 2019 | 63 | 71.4 | 63.5 | 46.0 | 34.4 | 485 | 52.4 | 57.1 | 55.7 | 33.5 |

| 2010 to 2016 | 119 | 58.0 | 62.2 | 58.0 | 26.6 | 794 | 48.1 | 54.9 | 56.3 | 16.4 |

| Pre-2010 | 48 | 45.8 | 41.7 | 62.5 | 18.2 | 880 | 44.7 | 57.2 | 68.0 | 11.4 |

| Polypharmacy status | ||||||||||

| Not reported | 125 | 56.8 | 58.4 | 52.8 | 23.5 | 1314 | 44.5 | 54.9 | 61.3 | 11.2 |

| Reported | 103 | 62.1 | 58.3 | 58.3 | 28.7 | 836 | 52.2 | 58.4 | 60.4 | 22.3 |

| Non-HIV comorbidities | ||||||||||

| 0 | 79 | 60.8 | 54.4 | 58.2 | 29.6 | 914 | 44.3 | 53.0 | 54.7 | 19.2 |

| 1 | 80 | 56.2 | 51.3 | 52.5 | 24.6 | 390 | 46.7 | 53.1 | 65.1 | 11.1 |

| 2 | 33 | 60.6 | 75.8 | 48.5 | 13.6 | 282 | 48.6 | 55.0 | 61.0 | 16.0 |

| 3 | 21 | 71.4 | 61.9 | 52.4 | 36.8 | 176 | 55.1 | 59.7 | 65.3 | 11.7 |

| ≥4 | 17 | 47.1 | 70.6 | 76.5 | 21.4 | 397 | 52.4 | 66.8 | 69.0 | 18.9 |

| Number of conditions taking medicines for | ||||||||||

| 1 | 136 | 60.3 | 53.7 | 53.7 | 21.6 | 1266 | 45.1 | 52.6 | 58.5 | 16.0 |

| 2 | 62 | 56.5 | 62.9 | 51.6 | 34.0 | 419 | 47.0 | 58.5 | 65.6 | 11.5 |

| 3 | 15 | 66.7 | 73.3 | 60.0 | 25.0 | 236 | 53.0 | 59.7 | 57.2 | 17.9 |

| ≥4 | 17 | 52.9 | 64.7 | 82.4 | 28.6 | 238 | 57.1 | 68.9 | 69.3 | 24.0 |

| ART formulation | ||||||||||

| Single tablet | 80 | 57.5 | 58.8 | 58.8 | 12.0 | 1071 | 43.6 | 57.0 | 65.0 | 10.8 |

| Multi-tablet | 148 | 60.1 | 58.1 | 53.4 | 32.2 | 1079 | 51.3 | 55.5 | 56.9 | 21.2 |

| Self-reported viral status | ||||||||||

| Non-suppressed | 78 | 62.8 | 64.1 | 52.6 | 31.0 | 541 | 49.4 | 53.2 | 51.8 | 32.8 |

| Suppressed | 152 | 57.2 | 55.3 | 57.2 | 23.2 | 1618 | 47.1 | 57.4 | 64.0 | 11.9 |

Figure 1

Percentage of participants who reported various perceptions and beliefs regarding drug-drug interactions and other aspects of care, by geographical region within pooled analysis of people living with HIV in all participating locations (N=2389)

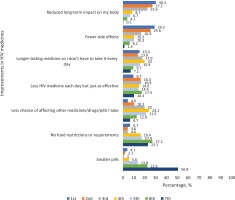

Among Asians who participated in the discrete choice experiment, 4.6% ranked the need to reduce DDIs in first place of importance relative to the other ART attributes assessed, 10.3% ranked it in second place, while 20.0% ranked it in third place (Figure 2). First, second, and third place rankings for ART regimens with less medicines each day but just as effective, were 9.7%, 16.4%, and 16.9%, respectively (Figure 2). Ranking of the seven ART attributes perceived as most important based on their cumulative shares of first, second, and third place positions were as follows among Asian participants: reduced long-term impact on my body (80.1%), fewer side effects (71.7%), ‘longer-lasting medicine so I don't have to take it every day’ (47.1%), less HIV medicine each day but just as effective (43.0%), less chance of affecting other medicines/drugs/pills I take (34.9%), no food restrictions or requirements (15.9%), and smaller pills (7.2%).

Factors associated with DDI-related experiences and perceptions

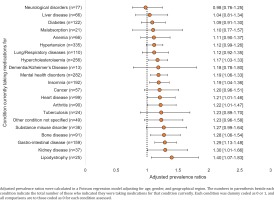

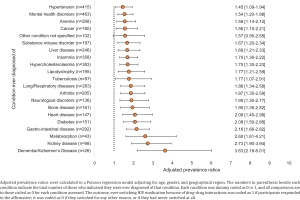

Following adjustment for region, age, and gender within a pooled analysis, current medical treatment for certain conditions increased the likelihood of being worried about the risk of DDIs (Figure 3). Compared to those not currently on medication for the specified conditions below, those currently on medication reported greater concern about the risk of DDIs with their ART: hypercholesterolemia (adjusted prevalence ratio, APR=1.17; 95% CI: 1.03–1.33), mental health disorders (APR=1.19; 95% CI: 1.06–1.33), insomnia (APR=1.19; 95% CI: 1.04–1.36), heart disease (APR=1.21; 95% CI: 1.01–1.46), arthritis (APR=1.22; 95% CI: 1.01–1.47), bone disease (APR=1.28; 95% CI: 1.06–1.54), gastrointestinal disease (APR=1.29; 95% CI: 1.13–1.48), kidney disease (APR=1.30; 95% CI: 1.01–1.66), and lipodystrophy (APR=1.40; 95% CI: 1.07–1.83) (all p<0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Adjusted prevalence ratios with 95% confidence intervals for self-reported concern over risk of drug-drug interactions, comparing individuals currently taking medications for each specified condition vs those not taking medications for that condition currently within pooled analyses of people living with HIV in all participating locations, 2019 (N=2389)

There was also a strong association between certain conditions ever been diagnosed (regardless of whether currently being treated), and a report of past DDI-induced ART switching (Figure 4). The strongest associations in this regard were noted for bone disease (APR=1.95; 95% CI: 1.35–2.82), heart disease (APR=2.08; 95% CI: 1.45–2.98), diabetes (APR=2.08; 95% CI: 1.50–2.88), gastrointestinal disease (APR=2.16; 95% CI: 1.66–2.82), malabsorption (APR=2.60; 95% CI: 1.61–4.21), kidney disease (APR=2.73; 95% CI: 1.90–3.94), and dementia/Alzheimer’s disease (APR=3.63; 95% CI: 2.19–6.01) (all p<0.05).

Figure 4

Adjusted prevalence ratios with 95% confidence intervals for report of having ever switched HIV medications on account of drug-drug interactions, comparing individuals ever diagnosed of each specified condition vs those never diagnosed of that condition within pooled analyses of people living with HIV in all participating locations, 2019 (N=2389)

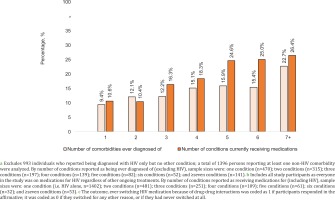

When expressing the outcome past DDI-induced ART switching as a percentage of all participants (not just those who switched), the probability of reporting this outcome increased with increasing number of comorbidities as well as with increasing number of concurrent treatments (Figure 5). The percentage of the entire pooled sample that ever switched ART because of DDIs ranged from 10.6% (148/1402) among those currently on ART only, to 26.4% (14/53) among those receiving medications for ≥7 conditions (including HIV). Consistent trends were seen when examining past DDI-induced ART switching in the entire pooled sample as a function of comorbidities ever diagnosed; this percentage ranged from 9.4% (44/470) among those with exactly one non-HIV comorbidity ever diagnosed, to 22.7% (32/141) among those with ≥7 non-HIV comorbidities ever diagnosed. Notably, even among those reporting they had never been diagnosed with any non-HIV comorbidity, 11.7% (116/993) still reported past DDI-induced ART switching.

Figure 5

Dose-response relation between number of non-HIV comorbidities ever diagnosed of a as well as the total number of conditions currently receiving medications for b, and the outcome of having ever changed HIV medications because of drug-drug interactions c within pooled analyses of respondents in all participating locations, 2019 (N=2389)

Of all participants in the Asian region who had been living with HIV for at least one year, 34.6% (71/205) identified the need to reduce DDIs as a treatment priority when they first started ART (China 40.0%, Japan 28.2%, South Korea 25.0%, Taiwan 46.9%); the same percentage overall, 34.6%, also identified this as a treatment priority now (China 33.3%, Japan 33.8%, South Korea 25.0%, Taiwan 44.9%). More so, 14.6% (30/205) of those living with HIV for at least one year did not consider the need to reduce DDIs as a priority when they first started ART, but now identified it as a current priority. Within pooled multivariable analysis using the full dataset, the recognition of the need to reduce DDIs as a current priority (regardless of perception at ART initiation), generally increased with increasing number of concomitant medications when compared to those on ART only; prevalence ratios, by range of concurrent treatments, were 1.58 (95% CI: 1.39–1.80) among those receiving medications for two conditions (including HIV), to 2.05 (95% CI: 1.65–2.55) among those receiving medications for ≥7 conditions (including HIV). In contrast, when the outcome was new concerns about DDIs, the relationship with the number of concurrent treatments was significant only to a certain threshold of concurrent treatments (≥4) after which increasing number of concurrent treatments was no longer statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2

Adjusted prevalence ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with reporting drug-drug interactions as a new treatment concerna, a current treatment concernb, or a report of having ever switched HIV medications because of drug-drug interactionsc within pooled analyses of people living with HIV in all participating locations, 2019 (N=2389)

| Independent variables | Indicated that reducing DDIs was a new treatment prioritya | Indicated that reducing DDIs was a current treatment priorityb | Ever changed HIV medication because of DDIs (i.e. past major DDI)c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APR (95% CI) | p | APR (95% CI) | p | APR (95% CI) | p | |

| Number of conditions currently receiving medication for | ||||||

| 1 (i.e. HIV only, reference category) | ||||||

| 2 | 1.32 (1.06–1.64) | 0.011 | 1.58 (1.39–1.80) | <0.001 | 1.38 (1.03–1.85) | 0.033 |

| 3 | 1.49 (1.15–1.94) | 0.003 | 1.67 (1.44–1.94) | <0.001 | 1.81 (1.31–2.49) | <0.001 |

| 4 | 1.83 (1.33–2.51) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.58–2.27) | <0.001 | 2.29 (1.47–3.57) | <0.001 |

| 5 | 1.27 (0.78–2.06) | 0.332 | 1.99 (1.62–2.44) | <0.001 | 3.40 (2.04–5.67) | <0.001 |

| 6 | 1.67 (0.99–2.82) | 0.052 | 2.18 (1.71–2.79) | <0.001 | 3.30 (1.75–6.23) | <0.001 |

| ≥7 | 1.25 (0.74–2.10) | 0.400 | 2.05 (1.65–2.55) | <0.001 | 3.68 (2.24–6.02) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <50 (reference category) | ||||||

| ≥50 | 1.19 (0.99–1.43) | 0.066 | 1.14 (1.02–1.27) | 0.022 | 0.75 (0.56–1.00) | 0.052 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (reference category) | ||||||

| Female | 0.92 (0.76–1.12) | 0.395 | 1.00 (0.89–1.11) | 0.950 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 0.908 |

| Binary/other | 1.00 (0.61–1.65) | 0.992 | 1.00 (0.75–1.33) | 0.980 | 0.76 (0.29–1.99) | 0.583 |

| Region | ||||||

| Asia (reference category) | ||||||

| North America | 1.27 (0.86–1.89) | 0.231 | 1.17 (0.94–1.46) | 0.166 | 1.12 (0.81–1.54) | 0.510 |

| Europe | 1.10 (0.76–1.60) | 0.623 | 1.09 (0.88–1.34) | 0.437 | 0.65 (0.46–0.90) | 0.010 |

| Latin America | 1.72 (1.13–2.62) | 0.012 | 1.22 (0.95–1.56) | 0.120 | 0.41 (0.24–0.67) | 0.001 |

| Other | 1.74 (1.19–2.56) | 0.004 | 1.36 (1.10–1.70) | 0.005 | 0.28 (0.17–0.47) | <0.001 |

| Year of HIV diagnosis | ||||||

| 2017 to 2019 (reference category) | ||||||

| 2010 to 2016 | 1.24 (0.93–1.66) | 0.144 | 1.17 (0.99–1.37) | 0.059 | 0.85 (0.67–1.09) | 0.208 |

| Pre-2010 | 1.54 (1.16–2.06) | 0.003 | 1.18 (1.00–1.40) | 0.053 | 0.67 (0.49–0.92) | 0.014 |

| Domicile | ||||||

| Metropolitan (reference category) | ||||||

| Non-metropolitan | 1.14 (0.95–1.35) | 0.151 | 1.03 (0.93–1.14) | 0.528 | 1.13 (0.91–1.41) | 0.260 |

| ART formulation | ||||||

| Single tablet regimen (reference category) | ||||||

| Multi-tablet regimen | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 0.740 | 1.03 (0.94–1.14) | 0.532 | 2.05 (1.60–2.63) | <0.001 |

| Education level | ||||||

| ≤High school (reference category) | ||||||

| >High school | 0.96 (0.79–1.17) | 0.679 | 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 0.522 | 1.14 (0.87–1.50) | 0.332 |

| Prefer not to answer | 0.91 (0.57–1.43) | 0.676 | 1.03 (0.79–1.34) | 0.848 | 0.36 (0.09–1.50) | 0.161 |

Adjusted prevalence ratios were calculated in a multivariable Poisson regression model that adjusted for all factors listed in table. Statistical significance was at p<0.05.

a Analyzed among the subset of individuals who were diagnosed for at least one year prior to the survey (n=2237). Participants were asked to select their treatment priorities at the time they started treatment as well as at the time of the survey. Reducing drug-drug interactions was deemed a new treatment priority if it was not selected as one of the priorities at time of starting treatment but was selected as a current treatment priority.

b Analyzed among the subset of individuals who were diagnosed for at least one year prior to the survey (n=2237). Reducing drug-drug interactions was deemed a current treatment priority if it was selected as such regardless of whether it was perceived as a priority at time of starting treatment.

c Analyzed among all participants (n=2389). Ever switching of HIV medication because of drug-drug interactions was coded as 1 if participants responded in the affirmative to the question; it was coded as 0 if they switched for any other reason, or if they had never switched at all. A past ‘major DDI’ with ART was defined in this study as complications with ‘medicines/drugs/pills for other conditions/illnesses’ that were severe enough to warrant a complete switch of the individual’s ART.

Older adults aged ≥50 years were more likely to perceive the need to reduce DDIs as a current treatment priority, than younger adults within pooled analysis (APR=1.14; 95% CI: 1.02–1.27). Compared to the Asian region, the adjusted likelihood of ever switching ART on account of DDIs did not differ significantly among participants in North America but was significantly lower among participants in Europe (APR=0.65; 95% CI: 0.46–0.90), Latin America (APR=0.41; 95% CI: 0.24–0.67), and other regions (APR=0.28; 95% CI: 0.17–0.47) (Table 2).

Associations between DDI experiences and health-related outcomes

When compared to those with no history/current concerns about DDIs within pooled multivariable analyses, those reporting past DDI-induced ART switching reported higher likelihood of suboptimal adherence (APR=1.91; 95% CI: 1.58–2.30) and lower likelihood of self-reported viral suppression (APR=0.73; 95% CI: 0.66–0.81). They also reported lower likelihood of optimal health on all assessed domains, including physical (APR=0.62; 95% CI: 0.54–0.72), mental (APR=0.71; 95% CI: 0.62–0.82), and overall (APR=0.65; 95% CI: 0.56–0.75), as well as lower likelihood of treatment satisfaction (APR=0.85; 95% CI: 0.77–0.94). Conversely, they were more likely to perceive room for improvement with their current HIV medication (APR=1.62; 95% CI: 1.40–1.87). Those with no report of a past DDI-induced ART switching but nonetheless concerned about the risk of DDIs also reported less favorable health-related outcomes when compared with those having no history/concerns about DDIs, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Adjusted prevalence ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the relationship between experience of drug-drug and various health-related outcomes within pooled analyses of people living with HIV in all participating locations, 2019 (N=2389)

[i] Adjusted prevalence ratios were calculated in a Poisson regression model adjusting for age, gender, geographical region, and presence of non-HIV comorbidities. DDI: drug-drug interactions; ART: antiretroviral therapy. A ‘past major drug-drug interaction’ was defined as one that was severe enough to result in a switch in HIV medications. Those who switched for reasons other than drug-drug interactions, or who never switched at all, were classified as not reporting a significant past drug-drug interaction. Concern about the risk of drug-drug interactions with ART was defined as a response of ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly agree’ to the statement ‘I worry how my HIV medicines will affect other medications/drugs/pills I take’.

DISCUSSION

Nearly 3 in 5 of our study participants from the Asian region (59.1%) were worried about the risk of DDIs with their current ART with variations noted within the region. Consistent with previous reports, older adults reported more comorbidities than younger ones, and the probability of having switched ART because of DDIs in the overall population increased with increasing number of comorbidities and concurrent treatments2,9. Concerns about DDIs may not necessarily be triggered by actual experience of DDIs, but increased treatment literacy in relation to potential side effects, which then might increase awareness of the risk of potential DDIs. Of the concurrent treatments assessed in our study, those most strongly associated with having concerns about the risk of DDIs with ART were for treatment of bone disease, gastrointestinal disease (e.g. ulcers), kidney disease, lipodystrophy, arthritis, heart disease, insomnia, and mental illness; this is in alignment with previous work documenting the types of medication most likely to cause DDIs with ART20. Taken together, there is need to carefully consider chronic conditions which may require long-term medical management and predispose patients to polypharmacy, particularly those individuals with multi-morbidities. Providing simpler regimen options such as those with fewer medicines, may reduce the risk of DDIs, especially among the elderly. Meeting the fourth ‘90’ target of improving health-related quality of life among PLHIV, calls for holistic care that considers patients’ concerns, comorbidities, priorities, and preferences when starting or switching HIV medication to minimize the impact of HIV treatment on day-to-day aspects of life6,8.

We found a statistically significant association between past DDI-induced ART switching and poor self-reported viral control, underscoring the need for intensified efforts to deliver holistic care. We also observed that 4.6% of PLHIV in the Asian region ranked the need to reduce DDIs as the number one treatment priority in their HIV care; this estimate might be suggestive of the percentage of PLHIV currently experiencing red-flag interactions. While this cannot be ascertained from the data, it is nonetheless similar to estimates from other PLHIV populations (e.g. 2% in the Swiss Cohort2, 4% in a Belgium study21, and 7% in a US study22). Over 2 in 5 of PLHIV in the Asian region were, however, not comfortable discussing DDIs with their healthcare providers, underscoring the need for providers to take proactive steps to include better communications as part of their treatment plans, especially as PLHIV grow older. Healthcare providers can positively impact ART initiation and adherence by tailoring treatment to address specific concerns patients may have about ART, including DDIs16. They can also provide patients with information on new treatment options to help them make well-informed decisions. Besides virologic control, considering patients’ preferences in relation to quality of life can accelerate progress towards reaching the global and national targets related to improving adherence and quality of life as espoused in the proposed fourth ‘90’ target aimed at delivering person-centered care to improve health-related quality of life.

In our study, the likelihood of having new concerns about DDI risks was significantly higher among those with comedications in addition to ART versus on ART exclusively, but as the number of concurrent treatments grew (beyond four), no significant difference was seen in new concerns about DDI risks. Individuals with a plethora of comedications may have developed coping mechanisms by virtue of possibly having managed polypharmacy longer and may not have any new concerns. Given however that drug effects can change over time4,22, it is critical for PLHIV and their healthcare providers to routinely discuss side effects and DDIs which the patient may be experiencing. We also observed that even among PLHIV who reported never been diagnosed with any non-HIV condition, 11.7% still reported past DDI-induced ART switching. Possible explanations include DDIs occurring from the use of complementary and alternative medicines, natural health products, and over-the-counter products for relief of ailments for which a formal diagnosis was never made ‘by a doctor or other healthcare professional’23,24. DDIs may also have occurred from the use of recreational drugs, including the misuse of prescription substances25. Finally, the list of conditions assessed in the survey was finite and may not have captured the full spectrum of diagnosed conditions that participants took medications for.

Limitations

Some limitations exist to this study. First, these are cross-sectional, self-reported data and only associations can be drawn. Second, the data may not be fully representative of the respective geographical regions because of the non-probabilistic sampling. Furthermore, the use of pooled data to generate estimates means that the results may not be representative of any specific country or region (e.g. the Asian region). Finally, there were no data on which specific medicines participants were taking for the condition(s) assessed; data only existed for the conditions for which medicines were being taken. Thus, our indicator of ‘concurrent treatments’ merely reflects counts of comorbidities being treated, not actually co-medications. Also, the list of health conditions assessed was not exhaustive. Finally, this study did not consider interactions between ART and herbal treatments.

CONCLUSIONS

A significant unmet need remains for PLHIV relating to DDIs, especially among individuals with comorbidities and concomitant medications. ART with reduced DDIs, and regimens with less medicines in them were ranked high as important treatment priorities among PLHIV in Asia. Healthcare providers can positively impact ART initiation and adherence by tailoring treatment to address specific concerns patients may have about ART, including DDIs and by prioritizing conversations that are person-centered.