INTRODUCTION

People living with HIV (PLHIV) are now living longer lives, and consequently, experiencing higher prevalence of comorbidities as they grow older1, 2. Given the complex relationships among HIV, HIV-related conditions, and mental health3, the fragmentation of healthcare into silos of care – general vs HIV – is inconsistent with person-centered care. Although comorbidities and polypharmacy adversely impact health outcomes, disease-oriented practice continues to be the prevailing approach to care4, 5. This is true despite treatment guidelines warning that patients with multiple conditions are more likely to experience adverse drug-drug interactions (DDIs) when treated with multiple, complex drug regimens6.

In terms of comanaging comorbidities within clinical settings, progress has been made in the broader context of workforce development and in sharing electronic patient information across traditional disciplinary silos7, 8. However, much remains to be done to make interdisciplinary approaches the standard of care in treating and managing HIV. A better understanding of how comorbidities, comedications, and polypharmacy together influence treatment choices among both PLHIV and HIV care providers is therefore critical for integrated healthcare planning4, 9.

Previous studies have examined the association between polypharmacy and indicators of health-related quality of life3, 10-13. It is, however, not well known how experience of comorbidities and polypharmacy influence patients’ treatment-related behaviors when it comes to starting, stopping, switching, or skipping ART doses. This has significant implications for the global 95-95-95 targets set out by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) to diagnose 95% of all PLHIV, provide ART for 95% of those diagnosed, and achieve viral suppression for 95% of those on ART14. A fourth target has been proposed to achieve good quality of life among 90% of all PLHIV15. The fourth target is intimately tied with the subject of polypharmacy and comorbidities as it places emphasis on not just clinical outcomes, but the overall wellbeing of PLHIV, including their fears, concerns, values, and treatment preferences. This study examined the inter-related issues of comorbidities, comedications and polypharmacy from both patient and provider perspectives to bridge any gaps in perceived unmet needs. We explored two questions: 1) ‘To what extent do comorbidities and concurrent medications influence the HIV care cascade in relation to starting, stopping, switching, or skipping ART?’; and 2) ‘What are the associations between polypharmacy and ART-related concerns and behaviors among PLHIV?’. To answer these questions comprehensively, we analyzed surveys of both PLHIV and HIV physicians in France, Germany, Italy and the UK, which were conducted during 2019.

METHODS

Study population/sampling approach

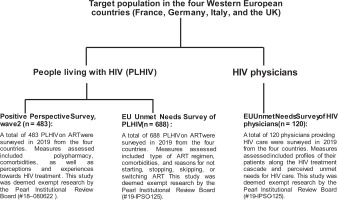

This was a secondary analysis of data from three surveys of HIV healthcare providers (HCPs) and/or PLHIV, which were all conducted in 2019 (Figure 1).

HCP Unmet Needs Survey

Within each of the four countries, 30 HIV physicians completed a web-based survey, yielding a pooled sample size of 120 physicians16. Inclusion criteria were: 1) Board certified/eligible physician with ≥5 years of practice as an internist or HIV/infectious disease specialist; 2) personally managed ≥50 unique HIV patients and saw ≥15 weekly. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The survey collected information on HCPs characteristics (e.g. clinical speciality and years in practice), as well as the demographic and clinical characteristics of their HIV patients (e.g. retention in care, on ART, and viral suppression profiles).

PLHIV Unmet Needs Survey

Across the four countries combined, a non-probability sample of 688 PLHIV on ART was selected (France, 144; Germany, 198; Italy, 150; UK, 196)16,17. Inclusion criteria were: 1) aged ≥18 years; and 2) confirmed HIV status, e.g. photograph of their HIV medication/prescription with their name on it. Most (60–70%) of PLHIV were recruited from existing panels of confirmed HIV sero-positive individuals; the remainder were recruited from national, regional, and local charities/support groups; online support groups/communities and social media platforms. Participants provided informed consent and completed the surveys online.

PLHIV Positive Perspectives Survey, Wave 2

The second Wave of the Positive Perspectives Survey was conducted in 25 countries, including France, Germany, Italy, and the UK13, 18-22. The entire 25-country survey comprised 2389 participants; the combined sample size from France, Germany, Italy and the UK was n=483 (France, 120; Germany, 120; Italy, 120; and UK, 123). Sampling was non-probabilistic. Participants were recruited by using targeted and snowball sampling approaches across multiple platforms and in collaboration with multiple HIV organizations. To be eligible, participants had to be aged ≥18 years and to verify that they were HIV sero-positive and receiving treatment (e.g. by presenting their ART prescription or a letter from their medical provider). Responses to the survey were collected over the web.

Measures

HCP Unmet Needs Survey

The HCP survey assessed perceived reasons among HCPs for their ART-naïve patients not starting treatment as well as their ART-experienced patients stopping, switching or skipping treatment. For the assessed reasons, an affirmative response was: 'Often', or 'Very often' (vs 'Sometimes', 'Never', or 'Rarely').

PLHIV Unmet needs survey

Participants were asked if they were ‘currently taking any antiretroviral treatment’, number of times they had made any changes in their ‘HIV treatment (i.e. combination of drugs) since diagnosis’, and reasons for changing treatment. Information was also collected on the specific HIV medications respondents were currently taking; this was classified based on the core agent reported (non-mutually exclusive categories), as an integrase strand inhibitor [INSTI], a boosted protease inhibitor [PI], or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [NNRTI]23:

1. NNRTI-containing regimens included: Atripla® or generics (emtricitabine/efavirenz/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate), Delstrigo (doravirine/lamivudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate), Edurant (rilpivirine), Eviplera (emtricitabine/rilpivirine/tenofovir -disoproxil fumarate), Viramune or generics (Nevirapin), Sustiva or generics (efavirenz), Odefsey (emtricitabine/rilpivirine/tenofovir alafenamide), or Pifeltro (doravirine).

2. PI-containing regimens included: Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir), Evotaz (atazanavir/cobicistat), Prezista (darunavir), Reyataz (atazanavir), Rezolsta (darunavir/cobicistat), or Symtuza (darunavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide).

3. INSTI-containing regimens included: Genvoya (elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide), Tivicay (dolutegravir), Triumeq (dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine), Isentress (raltegravir), Juluca (dolutegravir/rilpivirine), Stribild (elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate), or Biktarvy (bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide).

Past experience of a drug-drug interaction (DDI) was defined as reported ‘complications with medications … for other conditions/illnesses’ that culminated in either virologic failure (from non-adherence) or a regimen switch. Similarly, a history of resistance to ART was said to be present if this was reported as the reason for the respondent having stopped ART, switched ART, or failed to achieve viral suppression; or if the respondent was currently on Fuzeon (enfuvirtide), whose main indication is for treatment-experienced patients with evidence of HIV-1 replication despite ongoing ART24.

A history of a major side effect was said to be present if the respondent reported a past adverse effect from HIV medication (e.g.‘stomach/gastric problems because of the medication’ or ‘difficulties taking my HIV treatment as I was having too many side effects’), that led to stopping ART, switching ART, or failing to achieve viral suppression from non-adherence. Difficulty swallowing (i.e. dysphagia) that was elicited by the medicine directly (e.g. size of the pill) and not from an underlying medical condition was also classified as a side effect of the medicine, consistent with a published review of differential diagnosis of dysphagia25. Data were also collected on comorbidities, both their number and the organ systems affected.

PLHIV Positive Perspectives Survey, Wave 2

Consistent with previous research, we defined polypharmacy as taking ≥5 pills a day or taking medicines for ≥5 health conditions13. Self-rated overall health and its composite domains was assessed by asking participants: ‘How would you describe your physical/mental/sexual/overallhealth over the past 4 weeks?’. Response options were the same for physical, mental, sexual, and overall health: very poor, poor, neither good nor poor, good, or very good. Self-ratings of good, or very good were classified as optimal health on that domain; all other responses were classified as suboptimal. Self-reported viral suppression was assessed with the question: ‘What is your most recent viral load?’. Those answering ‘undetectable/suppressed’ were classified as ‘virally suppressed’.

Participants were asked reasons for missing ART at least once in the past 30 days, or ever switching ART. Data were also collected on various ART-related concerns, comorbidities, and perceived current treatment priorities. The last was assessed among those who had been diagnosed for at least one year and was measured as follows: ‘Imagine that you were starting HIV treatment today, other than ensuring that it is effective, what would be your most important considerations?’. Response options were: ‘To ensure that the virus was suppressed enough so that I could not pass it on to a partner’; ‘To ensure side effects would be minimal’; ‘To ensure it was compatible with other medications/drugs/pills I am taking’; ‘The cost of the medication’; ‘To keep the number of HIV medicines in my treatment to a minimum’; ‘To minimize the long-term impact of HIV treatment’; ‘To allow flexibility as to when I have to take the HIV medication (time of day, with or without food, etc.)’; ‘That the treatment is available in my public health facility’; ‘To manage symptoms or illnesses caused by HIV’; and ‘To have the best option to allow me to have children’.

Analysis

For the HCP Unmet Needs Survey, the unit of analysis was the individual HCP for outcomes involving the physician’s perceptions, and their the managed patients for the outcomes involving number and percentage of patients that met a characteristic of interest. Analysis for patient-related outcomes among HCP were restricted to only those HCPs indicating they had patients with that characteristic. Analyses assessed HCP-reported proportion of their ART-naïve patients who had not yet started ART (n=107 HCPs); the proportion of their ART-experienced patients who had stopped ART (n=85 HCPs), and reasons for not starting or stopping, respectively. All estimates from both PLHIV surveys (i.e. Unmet Needs and Positive Perspectives) had the individual respondent as the unit of analysis, and all analyses were among those currently on ART. Exploratory multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to assess factors associated with past DDI experience using data from the Unmet Needs Study. Because of high polychoric correlation (>0.3) between several independent variables, separate logistic regression models were fitted for each characteristic, adjusting for country of residence, age, gender, and sexual orientation. In the Positive Perspectives Study, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were calculated to measure the relationship between polypharmacy and various ART-related concerns, switching patterns, and reasons for missing ART, adjusting for age, gender, country, and presence of comorbidities. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS, Cary, NC, v9.4 and R v3.4.

RESULTS

Provider perceptions and experiences from the HCP Unmet Needs Study

Of the 120 HCPs surveyed, 25% came from each of the four countries. Of HCPs overall, 55.8% were infectious disease doctors who cared for a variety of infectious conditions not just HIV (France 36.7%, Germany 56.7%, Italy 93.3%, and UK 36.7%). A further 36.7% in the pooled HCP sample were HIV/AIDS specialists exclusively (France 50%, Germany 36.7%, Italy 6.7%, and UK 53.3%). The remainder of the pooled HCP sample practiced either internal medicine (5.0%) or genito-urinary medicine (2.5%). Regarding the treatment experience of the HIV patients they were currently managing, HCPs estimated that 85.7% of their patients were on ART (France 89.6%, Germany 85.7%, Italy 87.8%, and UK 79.6%) while 9.4% of their patients were estimated as having never initiated ART since they were diagnosed (France 7.7%, Germany 8.2%, Italy 8.4%, and UK 13.2%). Patients who had started but discontinued ART after diagnosis, were estimated by HCPs to be 5.0% of their total patient pool (France 2.7%, Germany 6.1%, Italy 3.8%, and UK 7.2%). The joint distribution of patients who were on ART and virally suppressed was 83.9% of their total patients (France 88.8%, Germany 81.0%, Italy 87.7%, and UK 78.2%).

Over half (53.3%, 57/107) of HCPs with newly diagnosed HIV patients not yet on ART indicated there was a plan to initiate treatment soon; however, 26.2% (28/107) felt there was no need to start treatment because HIV RNA and CD4 counts for the patient were within good levels, while 35.5% (38/107) cited patient unwillingness/undecidedness to start treatment as the barrier (Table 1). According to HCPs, challenges associated with comedications were a major reason for their patients not starting treatment, or stopping, switching, or skipping treatment after they started. In total, 16.8% of HCPs indicated that their patients had not started ART because of medical reasons/comorbidities that interfered with dosing (France 21.7%, Germany 15.4%, Italy 6.9%, and UK 24.1%). Other reasons cited by HCPs for patients not starting HIV treatment were: concerns about drug tolerability/side effects (overall 34.6%, France 39.1%, Germany 34.6%, Italy 27.6%, and UK 37.9%); concerns about long-term toxicities (overall 26.2%, France 39.1%, Germany 26.9%, Italy 24.1%, and UK 17.2%), as well as concerns about DDIs (overall 16.8%, France 13.0%, Germany 26.9%, Italy 17.2%, and UK 10.3%). Other reasons are given in Table 1.

Table 1

HCP perceptions regarding why some of their naïve patients have not started treatment, as well as why some of their patients on treatment stopped, or switched antiretroviral treatment, Unmet Needs Survey, 2019

Similar reasons were reported by HCPs for some patients stopping their HIV medications. These reasons included comorbidities that interfered with dosing (overall 11.8%, France 23.5%, Germany 13.6%, Italy 4.2%, and UK 9.1%), concerns over long-term toxicities (overall 29.4% France 41.2%, Germany 40.9%, Italy 20.8%, and UK 18.2%), and experience of DDIs (overall, 18.8%, France 23.5%, Germany 36.4%, Italy 4.2%, and UK 13.6%). Reasons for their patients switching ART from HCPs’ perspective are shown in Table 1, and included newer, safer and more efficacious HIV treatments becoming available (overall 56.6%, France 79.3%, Germany 43.3%, Italy 56.7%, and UK 45.8%), to reduce the number of pills the patients needed to take at the same time (overall 51.3%, France 69.0%, Germany 50.0%, Italy 46.7%, and UK 37.5%), to reduce the number of times per day the patient must take pills (overall 44.2%, France 62.1%, Germany 36.7%, Italy 30.0%, and UK 50.0%), to reduce the number of drugs within the treatment (e.g. two drug regimens; overall 42.5%, France 55.2%, Germany 50.0%, Italy 40.0%, and UK 20.8%), to reduce the risk of long-term toxicities (overall 62.0%, France 79.3%, Germany 50.0%, Italy 60.0%, and UK 58.3%), and because of other comorbidities that interfered with HIV treatment (overall 18.6%, France 24.1%, Germany 20.0%, Italy 10.0%, and UK 20.8%).

PLHIV’s perceptions and experiences from the PLHIV Unmet Needs Study

Among PLHIV currently on ART (n=688), 77.9% reported having ≥1 comorbidity in general, while 62.4% reported having ≥1 comorbidity that made taking ART challenging. Some PLHIV who were being managed medically for other conditions reported experiencing DDIs, with variations in DDI experience seen by number of comorbidities and type of ART regimen (Figure 2). Averaged across all ART regimen types, the percentage of PLHIV who indicated that they needed monitoring when taking other medications with their ART was 5.8%, 15.9%, and 24.1%, among those with none, 1, or ≥2 non-HIV comorbidities, respectively. Among those on ART with INSTI as a backbone, the corresponding prevalence was 7.3%, 14.6%, and 23.2%, respectively. Among those on ART with NNRTI as a backbone, the corresponding prevalence was 2.7%, 18.8%, and 30.4%, respectively. Among those on ART with protease inhibitors as a backbone, the corresponding prevalence was 5.3%, 20.8%, and 31.6%, respectively. Overall, 78.5% (540/688) of those currently on ART had changed their HIV medication ≥once (Table 2). Of those who changed, 31.7% reported switching because of availability of newer, safer and more efficacious treatments (France 27.2%, Germany 39.0%, Italy 38.7%, and UK 23.2%), 29.1% changed because of side effects (France 31.2%, Germany 24.3%, Italy 25.8%, and UK 34.2%). Others changed to reduce the risk of long-term toxicities (overall 23.3%, France 31.2%, Germany 15.4%, Italy 32.3%, and UK 16.8%), number of daily pills (overall 21.5%, France 23.2%, Germany 22.1%, Italy 25.8%, and UK 16.1%), number of medicines/drugs in regimen (overall 19.1%, France 24.0%, Germany 19.9%, Italy 24.2%, and UK 10.3%), or dosing frequency/day (overall 19.3%, France 19.2%, Germany 22.1%, Italy 16.1%, and UK 19.4%) (Table 2). However, 5.9% were asked to switch by their physician without an explanation (France 7.2%, Germany 6.6%, Italy 4.8%, and UK 5.2%).

Table 2

Reported reasons for treatment changes among persons living with HIV from four European countries who had ever changed their medication at least once, Unmet Needs Survey, 2019

Figure 2

Percentage of people living with HIV who reported various constraints with taking ART with other medications, by number of comorbidities and type of ART, Unmet Needs Survey, 2019

Among those on ART, prevalence of self-reported viral failure was 10.6% (France 22.9%, Germany 2.5%, Italy 19.3%, and UK 3.1%).

The percentage of PLHIV reporting past DDI and ART resistance was 11.3% (France 17.4%, Germany 7.1%, Italy 11.3%, and UK 11.2%) and 12.4% (France 17.4%, Germany 7.6%, Italy 17.3%, and UK 9.7%), respectively. Within adjusted analysis using the pooled sample, clinical characteristics associated with past DDI experience included being on an entry inhibitor (AOR=3.33; 95%CI:1.34–8.30), experiencing gastrointestinal side effects versus no side effects at all (AOR=1.84; 95% CI:1.06–3.20), and having ≥2 comorbidities than none (AOR=4.37; 95% CI:1.79–10.67) (Table 3). By specific comorbidities, adjusted odds of experiencing a DDI in the past were elevated among those reporting versus not reporting the following conditions: dysphagia (AOR=2.12; 95% CI: 1.25–3.59), gastrointestinal disease (AOR=2.10; 95% CI:1.27–3.48), and behavioral/substance use disorder (AOR=2.34; 95% CI:1.13–4.87).

Table 3

Prevalence and adjusted odds ratios for self-reported experience of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) among persons living with HIV in four European countries, Unmet Needs Survey, 2019

PLHIV’s perceptions and experiences from the Positive Perspectives Survey

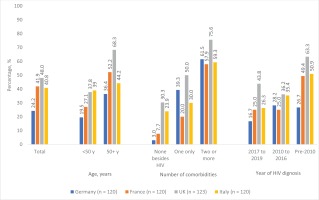

Within the Positive Perspectives Survey, overall prevalence of polypharmacy was 38.8% (France 41.9%, Germany 24.2%, Italy 40.8%, and UK 48.0%). As shown in Figure 3, prevalence of polypharmacy varied among population subgroups. For example, in France the percentage reporting polypharmacy was significantly higher among older adults aged ≥50 years (52.2%) than those aged <50 years (27.1%, p=0.011). Prevalence was 7.7%, 20.0%, and 57.9%, among French adults with none, 1, or ≥2 non-HIV comorbidities (p<0.001). By year of HIV diagnosis, prevalence was 25.0%, 25.0%, and 49.4%, among those diagnosed of HIV during 2017–2019, 2010–2016, and pre-2010, respectively (p=0.047).

Figure 3

Prevalence of polypharmacy, overall, and by selected characteristics among people living with HIV in four Western European countries, Positive Perspectives Survey, 2019

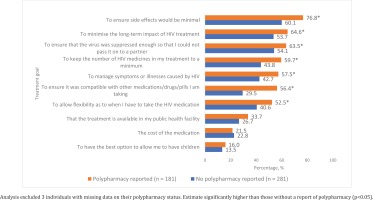

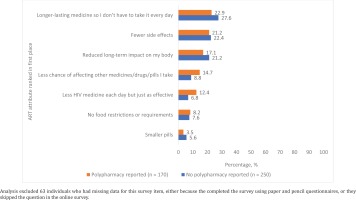

Systematic differences existed between those with and without polypharmacy in terms of their current treatment needs, reasons for past switching of ART, and observed patterns of missing ART. For example, among those diagnosed with HIV ≥1 year ago, a significantly higher percentage of those with polypharmacy reported that if they were to start HIV treatment today, they would prioritize the following: ensuring side effects would be minimal (76.8% vs 60.1%), minimizing the long-term negative impacts of their treatment (64.6% vs 53.7%), preventing HIV transmission to a partner (63.5% vs 54.1%), keeping the number of HIV medicines in their regimen to a minimum (59.7% vs 43.8%), managing symptoms or illnesses caused by HIV (57.5% vs 42.7%), ensuring their ART was compatible with other medications they were taking (56.4% vs 29.5%), and ensuring dosing flexibility (52.5% vs 40.6%) (all p<0.05) (Figure 4). When the entire sample was asked what they would rate as the most important improvement to HIV medicines, participants with polypharmacy were more likely to rate the following attributes in first place than those without polypharmacy: less chance of affecting other medicines (14.7% vs 8.8%), and less medicines each day but just as effective (12.4% vs 6.8%) (Figure 5).

Figure 4

Comparison of current treatment needs between PLHIV with and without polypharmacy among those diagnosed with HIV for at least one year in four Western European countries, Positive Perspectives Survey, 2019(N=465)

Figure 5

Percentage of people living with HIV who ranked the listed attributes in first place of importance, by polypharmacy status, among people living with HIV in four Western European countries, Positive Perspectives Survey, 2019

Within multivariable analyses adjusted for age, gender, country, and number of comorbidities, individuals with polypharmacy reported less favorable health outcomes and greater concerns about ART than those without polypharmacy (Table 4). Compared to those without polypharmacy, those reporting polypharmacy had lower odds of reporting viral suppression (AOR=0.40; 95%CI: 0.22–0.71), optimal physical health (AOR=0.44; 95% CI: 0.29–0.67) and optimal overall health (AOR=0.65; 95% CI: 0.43–0.99). In terms of ART-related concerns, those with polypharmacy were more likely than those without polypharmacy to report that they were worried about how taking HIV medicines for many years would affect their body/shape (AOR=1.50), of taking more and more medicines as they grew older (AOR=2.15), how their ART might affect other medicines they took (AOR=2.35), how their ART might affect their overall health and wellbeing (APR=1.77), as well as fearing they will run out of treatment options in the future (AOR=1.76) (all p<0.05). Systematic differences also existed between those with and without polypharmacy in their reasons for switching ART. Those with polypharmacy were more likely to switch because their previous ART was not sufficiently controlling their viral load (AOR=2.56), because of experiencing DDIs (AOR=4.13), and to reduce the number of medicines they needed to take (AOR=1.86) (all p<0.05). Differential reasons for missing ART in the past 30 days between those with versus without polypharmacy are shown in Table 4.

Table 4

Associations between polypharmacy and various treatment-related attitudes and behaviors among people living with HIV in four Western European countries, Positive Perspectives Study, 2019

DISCUSSION

Concerns about drug tolerability or side effects were major factors contributing to non-initiation, stopping, or switching of ART among PLHIV. Disparities were observed by various sociodemographic and clinical factors; for example, females had significantly higher prevalence of past DDI than males. Furthermore, DDI experience increased with increasing number of comorbidities. Providing simpler regimen options is important for all PLHIV, including the elderly, as they are more likely to encounter age-related comorbidities in addition to physical and cognitive challenges that could make adherence to complex regimens difficult26, 27. Previously identified leading comorbidities reported by PLHIV are chronic conditions which may require long-term medical management and predispose patients to polypharmacy, especially those individuals with multimorbidities13. Our results showed that individuals with polypharmacy were more likely to report suboptimal health in all domains, as well as suboptimal adherence and a variety of concerns over antagonistic or negative treatment effects. Meeting the fourth ‘90’ target of improving quality of life among PLHIV, calls for holistic care that considers patients’ concerns, comorbidities, priorities, and preferences when starting or switching HIV medication to minimize the impact of HIV treatment on day-to-day aspects of life15, 28.

The World Health Organization, and The European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) recommend a ‘treat all model of care (test and treat)’; according to EACS, ‘ART should always be recommended irrespective of the CD4 count’29, 30. Yet, 26.2% of HCPs felt there was no need to start treatment because their patients’ HIV RNA and CD4 counts were within good levels. More so, 35.5% of HCPs cited patient unwillingness/undecidedness to start treatment as the barrier to commencing ART. Healthcare providers can positively impact ART initiation and adherence by tailoring treatment to address specific concerns patients may have about ART, including treatment options that address identified issues such as concerns over immediate or long-term negative treatment impacts. HCPs can also provide patients with information on new treatment options to help them make well-informed decisions. Besides virologic control, considering patients’ preferences in relation to quality of life when planning treatment can accelerate progress towards reaching targets aimed at improving treatment adherence and quality of life15.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is exploring both PLHIV and HCP perspectives regarding barriers to the HIV care cascade in four countries that together account for the highest HIV burden in Western Europe31. Self-reported HIV diagnosis was followed by a confirmed ascertainment of HIV status for all PLHIV. Nonetheless, limitations exist. First, the HCP and PLHIV data in each country may not be directly comparable as the institutions from which the HCPs were mostly sampled from may not necessarily reflect places where sampled PLHIV routinely access care. Second, these are cross-sectional analyses and only associations can be drawn. Third, neither the HCP nor the PLHIV data may be fully representative of the respective countries or the region, because of the non-probabilistic sampling. Finally, our definition of polypharmacy was conservative as it did not fully account for all medications that participants may have been taking. While number of medications is strongly associated with number of diagnoses, they are not the same. For example, cardiovascular and pulmonary disease are likely associated with more medications than some other conditions. Future analysis should consider number of medications as well as number of conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

A significant unmet need remains for PLHIV relating to co-management of comorbidities and associated challenges such as polypharmacy. Among the four countries in Western Europe that participated in the study, prevalence of polypharmacy ranged from 24.2% to 48.0%. Polypharmacy was associated with suboptimal self-rated health, suboptimal adherence, and concerns about the risk of long-term negative/antagonistic impacts from ART intake. DDI experience increased with increasing number of comorbidities. Furthermore, DDIs and medical conditions that interfered with ART dosing were cited by HCPs as reasons for stopping, switching, or skipping ART. Simplified ART regimens with fewer medicines may help reduce the risk of DDIs and improve treatment adherence among PLHIV. Holistic care that provides simplified regimens to medically complex patients can help improve treatment outcomes.